GLOBAL HIGHER EDUCATION’S POST-COVID FUTURE (2) – FUNDING CHALLENGES FOREVER

| ALEX USHER

Yesterday, I described some of the big changes of the past 18 months; today I will talk a little bit about the first of the three big trends that we need to watch for over the next few years. This one I call “Funding Challenges Forever”.

Around the world, COVID has had two distinct financial impacts on institutions. In countries where the vast majority of funding came from governments (mainly, but not exclusively, Europe), the COVID shut-down had very little effect on institutional finances. The more immediate problems occurred in places where higher education institutions were more reliant on tuition revenue (and particularly international student revenue) and revenue from ancillary sources based on campus living/foot traffic. The two worst-hit countries were probably the United States and Australia, where funding shortfalls led to layoffs of more than 10% of each country’s higher education workforce.

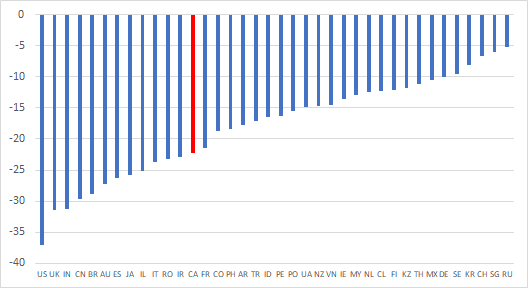

But in the longer term, COVID has a sting in the tail for higher education in publicly-funded countries, too. As Figure 1 (based on IMF data) shows, most countries around the world borrowed a boatload of money to get through the crisis. (Canada is in red). The more they borrowed, the less ability they will have to either pay for existing commitments in higher education or to increase them: and in countries where there is limited recourse to tuition fees, institutions will not be able to deal with this squeeze by turning to students as they do in Canada. So, the likelihood is that there will be a long, slow squeeze on institutional finances in many countries. The only bonus here – if you can call it that – is that most of the countries that went big into deficit in the 2020-2022 period were countries with tuition fees and thus institutions will be somewhat shielded from the effects of a government pull-back.

Figure 1: Net Borrowing as a Percentage of GDP, 2020, 2021 and 2022 Combined, Selected Countries

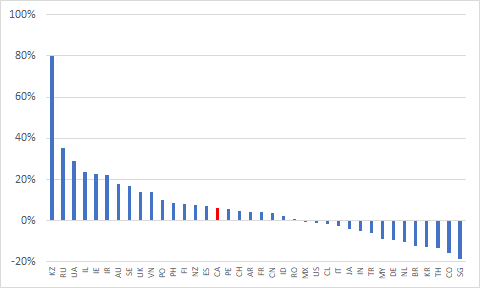

Now declining funding isn’t going to be the end of the world everywhere because in about a third of the world’s big higher education systems, the population they primarily serve (that is, the 18-21 population) is set to decline over the next decade. In fact, in six countries – the Netherlands, Brazil, Korea, Thailand, Colombia and Singapore – the decline in the prime higher education populations are going to be in the double digits. Think of these countries as really big New Brunswicks – overall funding will likely decline, but funding per student might stay steady.

On the other hand, as Figure 2 shows, there are a few countries that are looking at really big jumps in their tertiary-aged population. Australia, for instance, is looking at a jump of 18%, as is Iran. Ireland and Israel are both looking at jumps in the low 20%s. Ukraine and Russia – which experienced long declines in births after 1991 – are now suddenly seeing very sharp rises in the 18-21 population: a projected 29% and 35%, respectively, over the next decade. And Kazakhstan is looking at an eye-watering jump of 80%. Pandemic or not, these countries will need to invest a lot of money in their sectors over the next decade. But the COVID borrowing will make it harder.

Figure 2: Projected Change in population 18-21, UNDP Medium Variant, Selected Countries, 2020 to 2030.

The sweet spot in this situation is to have not added much debt during COVID (thus preserving a fair bit of fiscal maneuvering room) while also possessing a declining youth population and hence a smaller future client base. Countries in this group, which basically consists of Singapore, Korea, the Netherlands, Germany and Malaysia, will have comparatively more flexibility to invest in higher education and will perhaps be able to focus on quality improvement. The flip side – the “Group of Death” if you will – is made up of those countries who have the inverse conditions: both growing youth populations and high levels of debt incurred during COVID. The key members of this club are Australia, Canada, Iran, Israel, Spain and the United Kingdom. These countries will be entering a period of growth in PSE demand with a significant drag on their ability to make investments. All the other countries are ranging from “mildly inconvenienced” in their ability to fund higher education to those that are “pretty screwed”.

Now, in countries where tuition fees and other forms of student revenue are an option for institutions, there are really two choices with the kind of public disinvestment that seems likely over the next few years. The first is to play it safe and just suck up the cuts. Universities can re-examine their business models and adjust to a long-run future in which universities are smaller, leaner and probably less ambitious, because the amount of money simply does not allow for anything else. In theory, this is what Australian universities claim to be doing (if the chat I heard at the Australian Financial Review Higher Education Summit last month is anything to go by).

Or, there is a second choice: universities can gird themselves to an ever-more vicious fight for “market-priced” students – that is those students who can be charged a rate which permits an institution to generate surpluses (international students, students in professional master’s students and continuing education students), which is to say a continuation of what Canadian universities have been doing for the last few years, only with an even thinner safety net. My guess is that institutions will largely try to go down route #2, assuming that they will all get above-average results. They won’t. There are a finite number of these “market-priced students” and not everyone is going to be able to attract them. Some will come out ahead, others will not.

But the alternative is simply slow decline. This is why I don’t really believe that Australian universities are all excited to re-examine their business models and look at how to make do without so much Chinese money, as they seem to want everyone to think they are doing. There are very few places with extra domestic billions to spend out there, and where there are (e.g. the Biden administration), as often as not, they want to spend the money to make existing spaces cheaper, not expand the number of spaces or make existing education better. There are many alternative business models out there, but only the ones which increase “market-priced students” will result in budget increases.

No matter what, in the world of Funding Challenges Forever, it is going to be a struggle.

0 Comments