Presidents and Professors Largely Agree on Who Should Lead Innovation

When San Jose State University’s president announced the expansion of a pilot program to use recorded lectures from two large MOOC providers, he thought his campus would appreciate being on top of a growing trend.

Instead, Mohammad H. Qayoumi’s announcement last spring was met with howls of protest from professors in the philosophy department. They worried that the experiment would both put them out of work and provide a substandard education to their students.

Such dust-ups contribute to the rolling narrative that relations between faculty members and administrators have never been worse. Debates over technology, MOOCs (massive open online courses), and the very future of higher education have raised tensions on many campuses. Indeed, more no-confidence votes against college presidents were taken in the past academic year than in any one year in recent memory.

But according to an extensive survey of professors and presidents conducted this summer by The Chronicle, the two groups actually agree more often than not on some of the most contentious issues facing higher education, including the pace of change, who should lead innovation on campuses, and what many perceive as the negative impact of MOOCs.

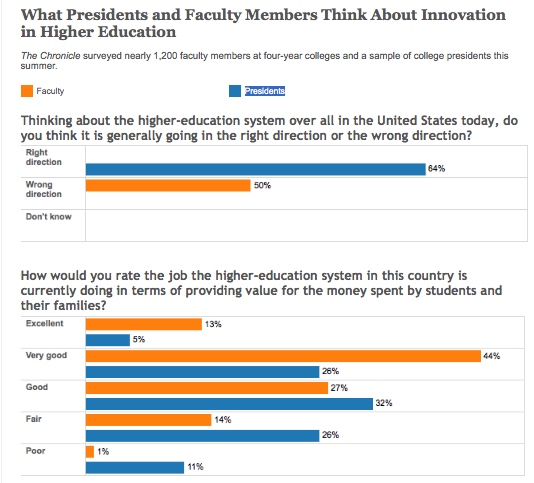

Where the two sides often disagree is more on a universal level—namely, where academe is headed in the next decade, and whether it provides good value for the money.

Faculty members are more pessimistic about the future of higher education. Only one-third of professors surveyed said American higher education was headed in the right direction, compared with two-thirds of presidents.

Among those most uncertain about the future are faculty members in the humanities (where departments have seen a decline in prestige), those at public research universities (which have seen sharp cuts in state subsidies), and those who have been teaching for more than 20 years (whose memories stretch back to higher education’s boom years of the 1960s and 70s).

The faculty members most optimistic about the future are those teaching in the STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—where government support has been high for much of the past decade.

What’s more, faculty members are more aligned with the public than with presidents on the question of value for the money spent on higher education. In the survey, only 31 percent of faculty members thought the higher-education system was providing “very good” or “excellent” value for the money spent, compared with 57 percent of presidents.

The Chronicle survey, completed by nearly 1,200 faculty members at four-year colleges and some 80 presidents of four-year institutions, was conducted by Maguire Associates, an education-consulting firm in Concord, Mass. The survey—complete results will be published this fall—focused on innovations in higher education, including the roles that various constituencies play in advancing ideas, as well as their opinions on online learning, hybrid courses, and competency-based degrees.

Professors and presidents are more in sync about the pace of change in higher education. Although colleges are often perceived by outsiders as stagnant, both faculty members and presidents in the survey agreed that colleges were more innovative than the public gives them credit for. Nearly half of both groups said colleges fostered a “moderate amount of innovation.”

At the same time, professors and presidents agreed that the pace of change was too slow in higher education. Fifty-four percent of presidents and 57 percent of faculty members said change was “too slow” or “far too slow.” As a result, a little more than a third of college leaders and faculty members agreed that higher education would be much the same in 10 years.

When it comes to driving change in higher education, faculty members overwhelmingly believe that while they should be leading the discussion, politicians were often the ones pushing the agenda. Somewhat surprisingly, presidents also said faculty members should be driving change, and agreed that it’s often politicians who control the conversation.

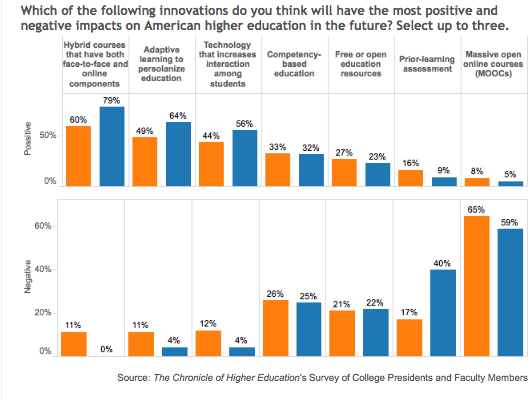

Among the innovations being discussed now, presidents and faculty members were most negative about MOOCs. Some 60 percent of presidents and 65 percent of professors think that MOOCs will have a negative impact on the future of higher education. Presidents and faculty members were most positive about the potential of hybrid courses. On the topic of competency-based learning, 51 percent of professors and 46 percent of presidents agreed that colleges should award credit based on what students know instead of time spent in a seat.

Over all, faculty members and presidents said that, when it comes to innovative practices, too much attention was given to technology and cost-cutting and not enough to improving teaching and learning.

0 Comments