What Makes an Inventor?

What Makes an Inventor?

PARIS – Who becomes an inventor? Ideally, it would be anyone with a natural talent for innovation. But what if talent in innovation is misallocated, because some potential inventors are deprived of the conditions for success? After all, in addition to natural endowments, much depends on one’s social environment, and not every potential inventor is afforded the same level of education or parental support.

In a recently published study, we set out to answer these and related questions. Specifically, by merging three comprehensive data sets, we were able to see how the income and educational level of one’s parents and one’s own talents can determine whether one becomes an inventor. We then analyzed the interaction between these factors, and concluded that talent in innovation is indeed at risk of being misallocated under certain conditions.

A PRIVILEGED CLASS?

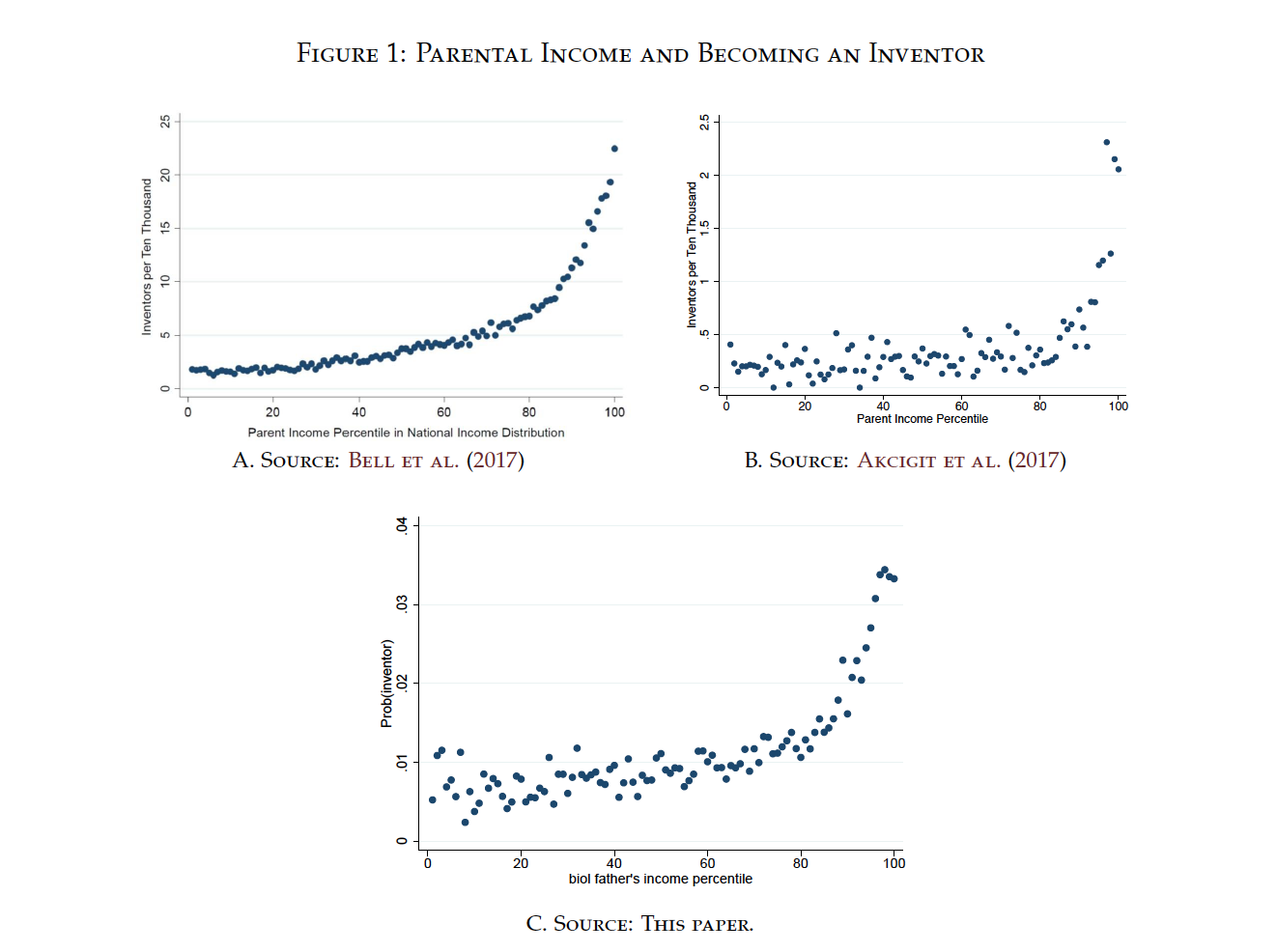

Before we turn to our own findings, consider the following figures, which show the effect of paternal income on the probability that an individual will become an inventor.

Figures 1A and 1B draw on US data, and Figure 1C draws on Finnish data. But in all three cases, the probability that someone will become an inventor clearly increases with paternal income. Moreover, the figures show that the effect is highly non-linear: the probability of becoming an inventor increases significantly at the highest levels of the paternal-income scale. In fact, children of fathers at the very top of the income distribution are ten times more likely to become inventors than those born to fathers at the bottom.

The similarity between Finland and the United States is striking. Unlike the US, Finland has low income inequality and high social mobility in international comparisons, and it offers free education up to and including university level.

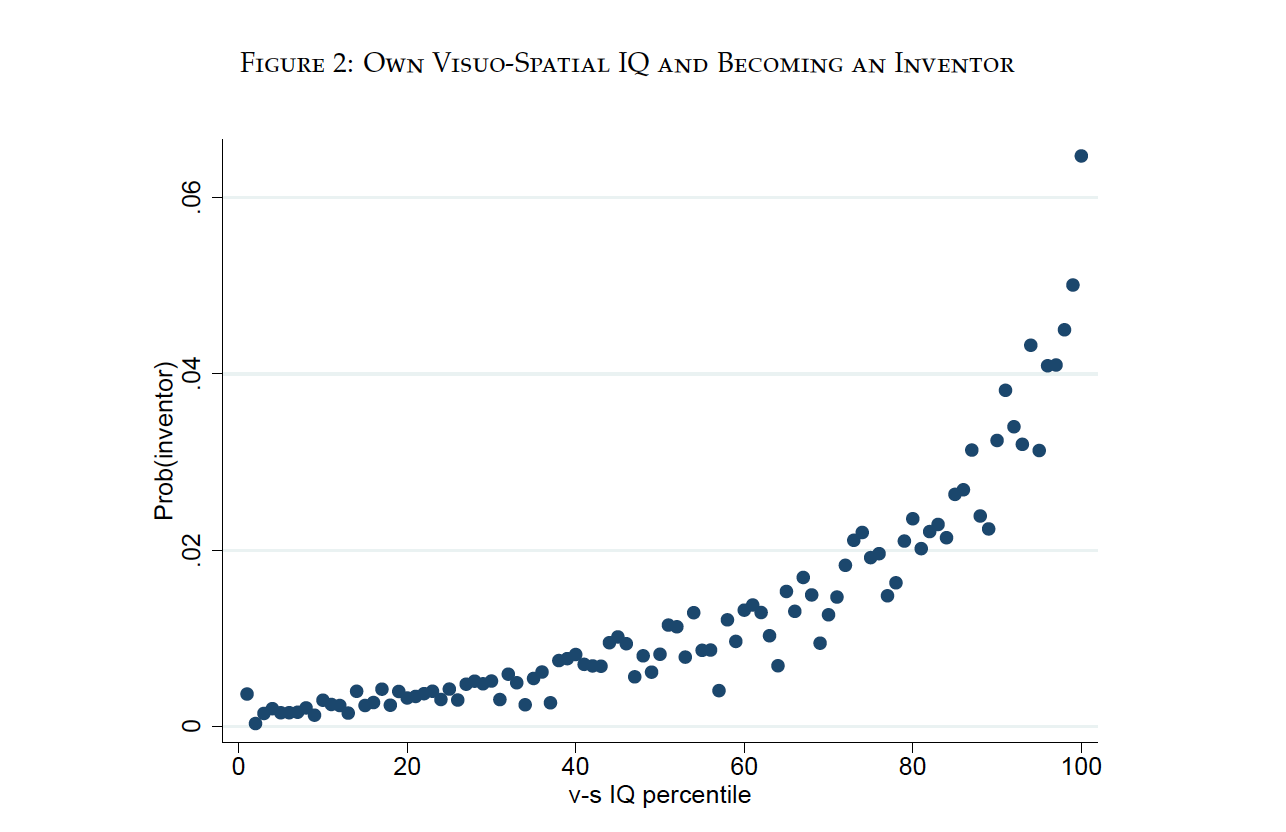

Now consider Figure 2, which shows that the probability of someone becoming an inventor increases with IQ. Those at the very top of the IQ distribution are five to six times more likely to become inventors than individuals in the middle.

WHAT THE DATA SHOW

What lies behind the steep relationship between paternal income and the probability of becoming an inventor? Does IQ matter more or less than family background? And how do these factors interact with each other?

Taken together, the three data sets that we merged shed light on the factors that matter most for creating innovators in the twenty-first century. The first data set, from Statistics Finland (SF), comprises individual statistics on Finns’ parental income, education, and socioeconomic status (a measure of whether at least one parent holds a white-collar management position). The second set includes patenting data from the European Patent Office. And the third provides IQ data from the Finnish Defense Forces, which conscripts only men, thus limiting our findings to the male work force.

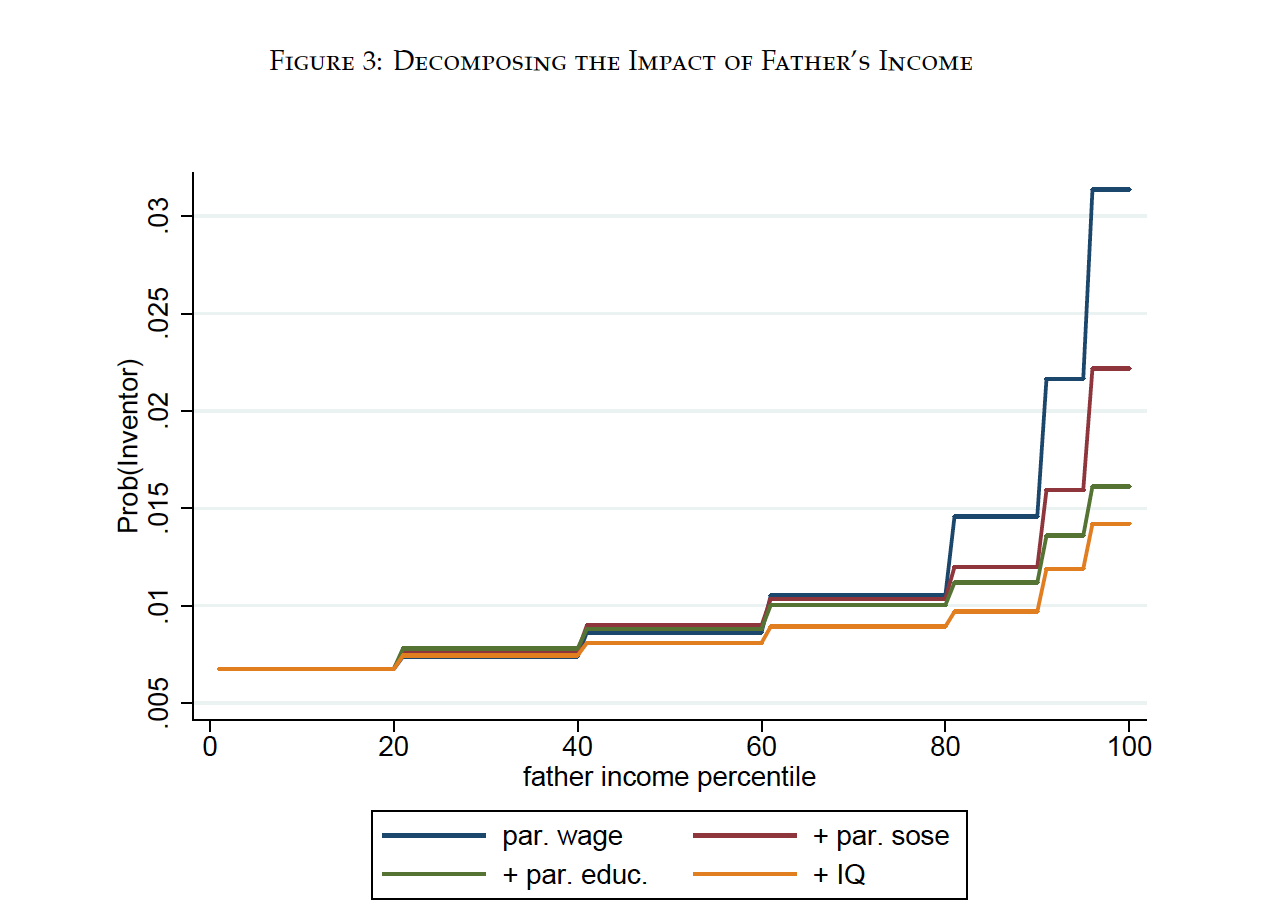

After merging these data, we determined that higher parental income does correspond to a higher probability of becoming an inventor; however, its estimated impact falls significantly after controlling for parental socioeconomic status and education, as well as individual IQ. This finding is illustrated in Figure 3, where the overall relationship between parental income and the probability of becoming an inventor is depicted by the upper curve.

On its own, the top curve in Figure 3 would suggest that parental income directly affects an individual’s chances of inventing something. But with each additional factor accounted for, the correlation between parental income and becoming an inventor flattens. This suggests that the apparent importance of parental income masks more complex channels that other studies examining “who becomes an inventor” have not considered.

For example, high-income parents typically enjoy a higher socioeconomic status, and tend to be more educated, which translates into more educational and training opportunities for their children. Moreover, higher-income parents may produce higher-IQ children who are more likely to innovate.

MIND OVER MATTER

A second finding from merging the data is that the effect of visual-spatial IQ on the chances of becoming an inventor is almost fivefold that of having a high-income father. We arrived at this conclusion by focusing our analysis on potential inventors with a brother close in age, which allowed us to control for family-specific time-invariant characteristics. It seems that IQ does not just have a robust effect, but can also operate rather independently from unobserved characteristics of family background.

THE YEAR AHEAD 2018

The world’s leading thinkers and policymakers examine what’s come apart in the past year, and anticipate what will define the year ahead.

It is interesting to compare the impact of parental income and individual IQ on the probability of becoming an inventor as opposed to a lawyer or physician. Assuming that everyone is in the top decile of the IQ distribution, the likelihood of individuals becoming inventors would increase by 183%, compared to just 86% for physicians, and 0% for lawyers. On the other hand, if everyone has a father in the top income decile, the likelihood of individuals becoming inventors would be just 30% higher, but 78% and 72% higher for lawyers and physicians, respectively.

Clearly, IQ is more important in determining who will become an inventor than in determining who will become a lawyer or physician. And for potential inventors, it is more important than parental income and education. But that is not to say that family background doesn’t matter. In fact, family structure can prove particularly important.

For example, when we compared individuals with either a missing biological parent or a stepparent, we found that the effect of parental income on the probability of becoming an inventor depends largely on whether the father lives with the individual. It turns out that individuals whose parents are divorced are less likely to become inventors, and individuals who grow up with a stepfather are even less likely. This suggests that, in some cases, the effect of one’s family background on whether one becomes an inventor can operate independently from IQ and ability.

Obviously, this points to a potential source of misallocation: namely, that there are individuals with very high IQs who will nonetheless underperform as potential innovators for want of parental resources or more conducive family structures.

To understand this point fully, consider two individuals, A and B, whose fathers both belong to the lowest income quintile. If A has an average IQ, but B has an IQ in the top 96th percentile, moving both individuals into households with a father in the top 96th percentile of the income scale will make B more than three times as likely as A to invent something. In other words, high-IQ individuals suffer disproportionately from inadequate parental resources and misallocation, which, in turn, erodes the innovative potential of the economy.

THE KEY INGREDIENT

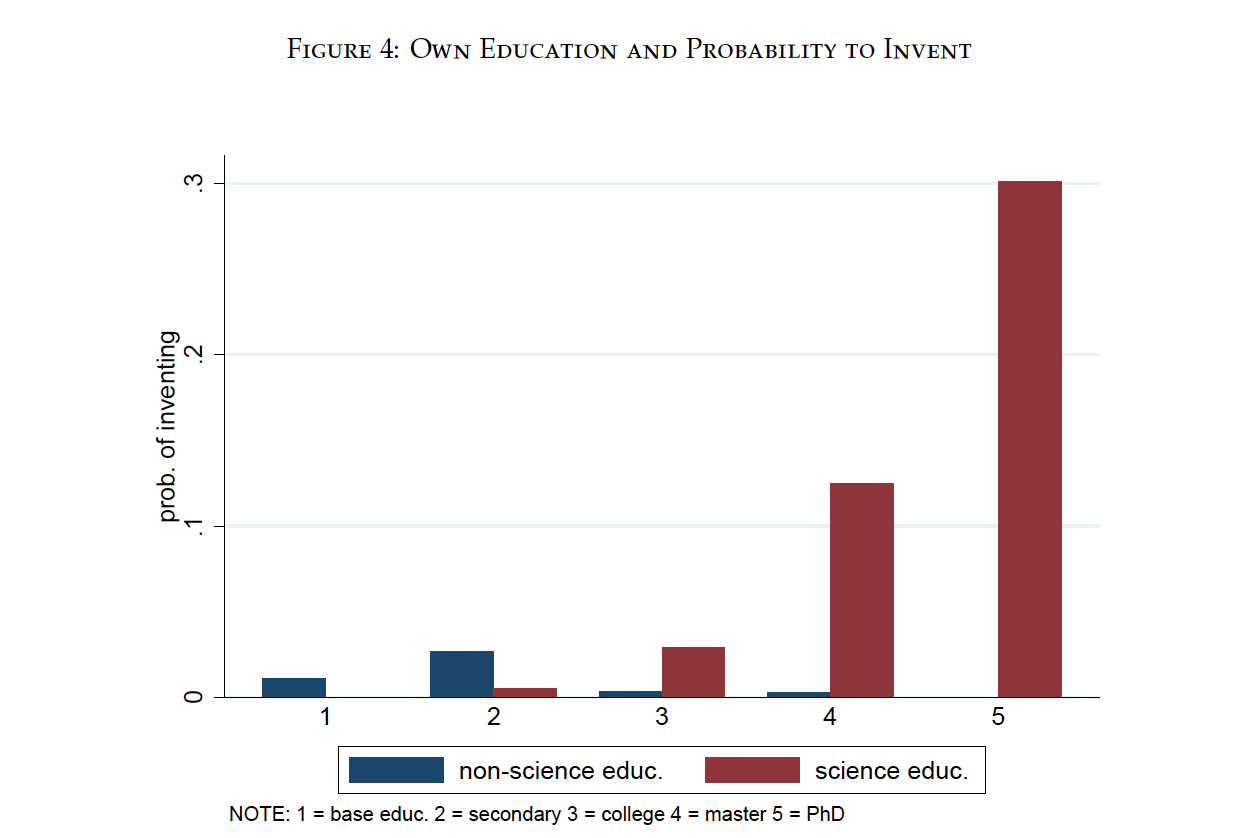

Education is, of course, a key area where parental income and IQ interact. As Figure 4 shows, completing a Master’s or PhD in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) has a stronger effect than any of the previously mentioned variables on whether one becomes an inventor. We calculated that, in terms of one’s chances of becoming an inventor, the effect of having a STEM Master’s degree is 25 times larger than that of having a father in the top 95th income percentile, ten times larger than that of having a father with a PhD, and six times larger than that of belonging to the top 95th IQ percentile.

But education is not randomly distributed. Only 10% of the individuals in our data set had a Master’s or PhD, and that attainment is itself a function of parental income, socioeconomic status, and education, as well as one’s own IQ. But which of these determinants matters the most? To answer that question, we looked at the role of each variable in explaining the variance in educational outcomes across individuals. We found that IQ accounts for 40% of the explained variation in individuals’ own education, followed by parental education, which accounts for 27%; parental income, meanwhile, trails behind, accounting for less than 5%.

Our results suggest that parental education and individual IQ – which operates directly and indirectly through educational attainment – both play a prominent role in determining whether someone will become an inventor.

THE TAKEAWAY

By merging data on individual IQ, patents, and parental income, education, and socioeconomic status, we were able to analyze how family background, natural ability, and the interactions between these variables determine whether one will become an inventor. We found that while parental income matters, even after controlling for background variables, its impact diminishes significantly once parental education and IQ are accounted for, and even more so when controlling for an individual’s own education. We also found that IQ has both a direct and an indirect impact, and that it plays a larger role in determining whether one becomes an inventor than it does for whether one becomes a physician or a lawyer.

0 Comments