The large for-profit college chain isn’t dead.

Stop the funeral dirges — or celebratory hymns, depending on where you fall on the political spectrum.

Yes, Corinthian Colleges hit bust. Yes, ITT Education Services is facing serious scrutiny from state and federal agencies that may yet shut down the chain. Yes, the new federal gainful employment rule will have an effect on the sector. And certainly enrollment numbers at many for-profit institutions are dropping. But the industry’s heralded doom is an exaggeration.

If anything, experts say it’s a course correction amid a climate of intense scrutiny and increased regulation.

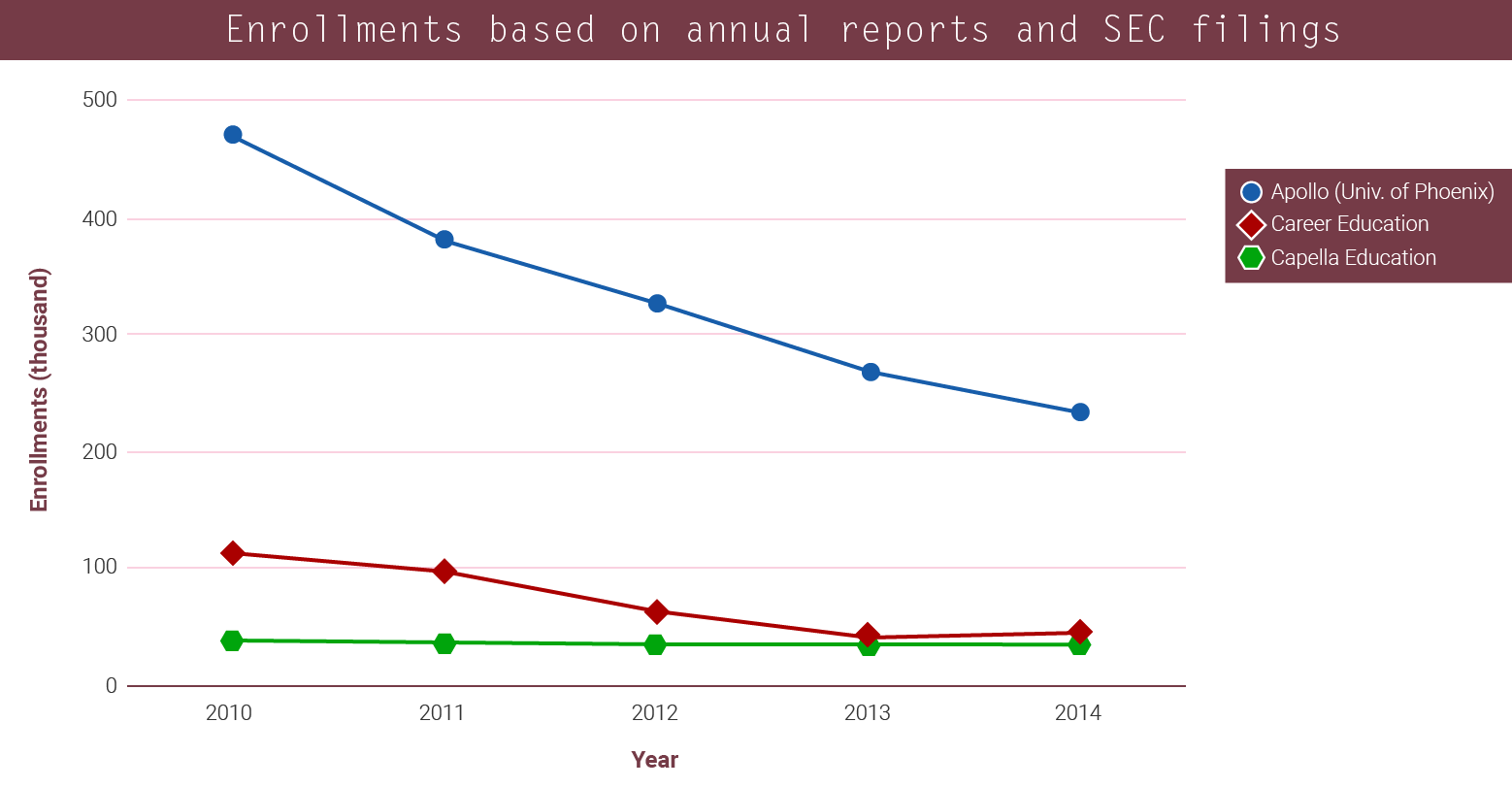

The decline is undoubtedly happening. According to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, for-profit student enrollment is down 4.9 percent compared to last spring. The enrollment decreases are playing a large part in driving down revenues and stock prices.

“It’s shrinking. Has been shrinking. Will continue to shrink. Things are getting less worse, but stabilization is a ways off,” said Jeff Silber, an education financial analyst with BMO Capital Markets.

But the demand for for-profit institutions is still there, even as enrollments fall from their peak in 2010, said Steve Gunderson, president and CEO of the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities (APSCU) — the for-profit sector’s primary trade group. In 2012, approximately 3.5 million students attended for-profit institutions. That figure is lower than the 4 million students who were enrolled in 2010, but still higher than the 2.6 million figure in 2007, Gunderson said.

Yet the massive changes in the sector have even shaken up APSCU, which is shifting to focus less on large for-profit chains and more on the nonprofit education sector as a few high-profile members leave the association. (See related article about its future.)

For-profit colleges have been around for at least 100 years in some form or another, but the current-day institutions are unique in that they’ve been providing degrees rather than the certifications granted by truck-driving or beauty schools, said Kevin Kinser, chair of the department of educational administration and policy studies at the State University of New York at Albany and an expert on for-profit higher education.

“What we might see is not the demise or complete collapse of publicly traded institutions, but a different focus for them,” he said. “A niche focus for them … a shift from degree granting to service providers. Maybe they have a higher education institution as part of the portfolio, but the portfolio is in the education service realm.”

Both Capella and Strayer Universities have managed to buck the trend of losing money and students by focusing on approaches experts say will keep the industry alive in the future. For instance, Capella has specialized in graduate degree programs for a long time, which has made them one of the more respected providers in the industry. Strayer found success in part through its partnerships with corporate clients.

“Predictions of the demise of the major publicly traded for-profit universities, colleges and education providers would be premature,” said Gary Rhoades, a professor and director of the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona. “But it is clear that a combination of consumer skepticism, competition from not-for-profit colleges and universities, and consumer protection actions by federal and state governments have reduced, not just market share, but also the image of for-profit higher education.”

If anything, the for-profit sector appears to be in the bust period of its regular boom-and-bust cycle. The last time the industry was in this level of turmoil was 25 years ago, when the government instituted tougher regulations and the sector readjusted, Kinser said. For-profits increased their enrollments dramatically in the 1980s and concerns arose around students defaulting and the amount of aid going to those colleges. So the federal government stepped in to regulate just how much federal money could go to for-profit institutions, among other things, he said — although many of those regulations were rolled back in the 2000s under the George W. Bush administration.

But the current bust cycle is more noticeable now than in the late 1980s and early 1990s because of how much larger the sector has grown. For-profits grew to take up about 10 to 13 percent of the education marketplace and also began offering more degrees, Kinser said.

“For-profits up until the 1990s were still predominantly non-degree-granting institutions … then we saw the transformation of the for-profit sector into the degree-granting sector and that’s why it became so prominent. It touched on what most people think of as actual college,” he said.

Responding to Rampant Growth

More attention than ever has been paid to the closure of for-profit colleges, as well as the heightened regulatory climate surrounding them. And the recovering economy and negative publicity haven’t helped with enrollment.

The rhetoric and regulations surrounding for-profit education, especially in Washington, have also become more profound. There certainly is a group of people who share the same view as Bob Shireman, who was recently announced as a senior fellow with the Century Foundation, that for-profits are fundamentally different and flawed. Illinois Senator Dick Durbin is one of them. He and other Senate Democrats, along with the Obama administration, continue to crack down on “bad actors.”

Some congressional Democrats are currently looking to close a financial loophole that they say benefits for-profits to the detriment of veterans and military students. That loophole is connected to the 90/10 rule that prevents for-profits from receiving more than 90 percent of their revenue from federal financial aid funds. Veterans’ education benefits do not count toward the limit.

But Steve Gonzalez, assistant director of the American Legion’s veterans employment and education division, doesn’t think for-profits should be singled out in closing that loophole.

“We’re looking to protect all student veterans, and we need to protect them regardless of what institution they go to,” he said, adding that altering the 90/10 rule still doesn’t ensure that the quality of an institution will improve.

There are also the new gainful employment rules that took effect this month, despite legal challenges from the for-profit sector aimed at stopping them. The regulations are a way to hold the colleges accountable for graduates’ ability to pay off their debt.

The U.S. Department of Education has estimated that about 840,000 students are enrolled in programs that would not pass the gainful employment metrics. Of those students, 99 percent are in programs at for-profit institutions. An APSCU report from last year detailed that many more students than that estimate would be affected.

Even so, experts said the rules will cull poor performers rather than spell the end of for-profits.

“There’s no reason to believe that the gainful employment rule, or any of these other enhanced performances for students and borrowers, will lead to the death of the industry,” said Debbie Cochrane, research director for the Institute for College Access and Success.

Recently the department appointed a so-called special master to oversee the process for former Corinthian students who are seeking debt relief by trying to prove they were defrauded by the company. That process may apply to other failed for-profits. But the expectation is that in the future if a large number of students are hurt by a different for-profit, the department will be able to recoup its losses from the company itself.

But that can be worrisome if there isn’t a system that can handle mass bankruptcy and closure, Kinser said, “Our system is set up to handle the closure of institutions with low enrollments, but tens of thousands of students across wide geographic areas is much more difficult to handle.”

“I don’t see a bottom yet,” Kinser said. “There still seems a way to go before we have a system that has stabilized.”

Many look at ITT Educational Services as the next domino that might fall. The Securities and Exchange Commission recently filed fraud charges against the for-profit and two executives. The Education Department has required ITT to provide cash flow projections every two weeks along with other financial transactions, planned school closures and potential new programs.

“It would be interesting to see how the department approaches it. I don’t necessarily think they have an appetite for more [of what happened to Corinthian],” said Steve Burd, a senior policy analyst with New America’s Education Policy Program. “But they’ve also been talking a tough game.”

The department has indicated that, as other institutions are headed in the direction of Corinthian, they’re working to develop a process for recovering taxpayer dollars from institutions found to be at fault.

Burd said those campuses and academic programs that have shut down, including Corinthian and ones at Education Management Corporation (EDMC), which has closed 15 of its 52 campus locations, failed to change or were unwilling to change their model.

“The industry has to move from growth at any cost,” he said.

EDMC officials declined to comment.

In Transition

Apollo Education Group has seen dramatic decreases in enrollment and revenue. The publicly traded company, which owns the University of Phoenix, most recently announced an 18.8 percent, or $379.3 million, drop in revenue during the nine-month period that ended May 31. Its enrollment also fell to 206,900 students by the end of May — a nearly 15 percent dip from the previous year.

In response, Phoenix announced a shift to a more selective admissions policy that could decrease enrollment further.

The company is piloting diagnostic tests that would examine student performance and determine whether someone is ready to attend Phoenix’s programs.

“At the end of the day we’re measuring academic preparedness so folks can earn a certificate en route to a diploma, en route to a good job or better job,” said Mark Brenner, Apollo’s senior vice president of external affairs. “We want the student experience to be the most important thing. It is our core belief that it’s in the student’s best interest to make sure they’re here and they’re a good fit. We’re helping them graduate from college and this will improve their outcomes. And helping students improve outcomes helps University of Phoenix be vibrant and healthy.”

The transition from being a sector focused on “growth” in students and revenues to a “value” sector is one many for-profits are facing. That can be painful for some, like Apollo. Investors care about growth, and the lack of it explains why stock prices have fallen, said Silber, the education financial analyst with BMO Capital Markets.

“They’re obviously hugely disappointed,” Silber said. “But the sector is now a value sector. As painful as it is, it’s healthy for the industry to focus on outcomes, graduation, retention … because the problem is the value proposition that this sector represents is just not being appreciated anymore. If you can prove these classes and degrees are worth taking and worth going into debt to have, it will benefit the longevity of the sector.”

But the expectation is that the renewed focus on outcomes and being more selective in admissions will rebuild Phoenix’s reputation and, in the long run, create a more viable economic model.

“There’s more demand on schools to focus on outcomes, and we’ve spent the last five years making sure the right people coming to University of Phoenix are coming for the right reasons,” Brenner said.

New Models

The for-profits don’t appear to be losing students to community colleges, which are also seeing enrollment decreases. But nonprofits in the online market are competing with for-profits as they increase their footprint.

“The demand is real and the community colleges are busy working out articulation agreements with four-year schools,” Gunderson said. “Look at the workplace. We need more workers with postsecondary certificates.”

Gunderson said the association is seeing more for-profit providers move into high schools or return to their roots as a sector by cutting back on the number of campuses or programs offered.

In fact, Kinser said, it’s not that for-profits are losing students to other education sectors. These potential students are choosing not to attend college at all.

“One of the things the for-profit sector has been very good at is they’ve been able to convince students who didn’t think of themselves as college material,” he said. “Rather than meeting an inherent demand, they were going out and creating demand.”

The competition from nonprofits is beginning to pick up steam. According to BMO, “Fifteen of the top 30 institutions with the largest online enrollments were not-for-profit schools, with many of them seeing increases in enrollment contrary to the annual declines seen by most for-profit schools.”

But even as many of the larger companies readjust or realign to meet this new reality, there are others that will continue to fall off.

“You’ll see some smaller schools that may not be able to afford all the infrastructure you have to apply with gainful employment,” Silber said.

And some providers may decide to stop accepting Title IV funds altogether, Gunderson said.

Take UniversityNow’s Patten University, for example, which has managed to keep tuition low by not participating in the federal financial aid program. For-profits are often criticized for high tuition prices, yet Patten’s online undergraduate tuition rate works out to $1,316 a semester.

After all, for-profit colleges that accept federal aid often charge students more in tuition.

Moving away from the all-encompassing, broader model to a more focused or niche approach is where many institutions are heading and where some like Capella already have arrived.

“We’re focused on working adults. They’re more affordable. More flexible. They deliver strong employment outcomes. That’s where the future is,” said Kevin Gilligan, Capella’s chief executive officer, adding that as a competency-based institution, the company believes in being accountable.

The negative publicity surrounding the for-profit market largely hasn’t affected the institution, and Capella has been at the table to talk about regulations and quality with the Education Department.

What effect these changes will have on students in the long term is still up for debate, although the hope is they’ll have more quality offerings.

“The industry will never be what it was. You’re never going to see the growth and investment dollars thrown at this sector like you did last decade,” Silber said. “But there are still viable businesses that offer something to a certain sector of the market.”

Enrollments at Degree-Granting

Four-Year For-Profit Colleges Annual Enrollment Growth (Decline)

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring Unduplicated Head Counts | 1,626,756 | 1,476,010 | 1,347,238 | 1,280,716 | 1,217,358 | |||

| 1Q13 | 2Q13 | 3Q13 | 4Q13 | 1Q14 | 2Q14 | 3Q14 | 4Q14 | |

| Bridgepoint Education | -17% | -22.6% | -24.9% | -22.2% | -18.1% | -14.7% | -13.1% | -12.3% |

| DeVry Education Group (undergrad) | -15.4% | -18% | -16.2% | -13.3% | -13.7% | -12.9% | -13.2% | -13.5% |

| ITT Educational Services | -14.2% | -11.7% | -7.1% | -5.8% | -6.4% | -5.3% | -6.4% | -6.8% |

| Strayer Education | -9.4% | 12.7% | -16.5% | -14.2% | -10.4% | -5.8% | -2.3% | -0.9% |

| Universal Technical Institute | -11.7% | -10.3% | -4.1% | -5.3% | -0.7% | -3.1% | -4.9% | -6.9% |

0 Comments