Preparing Students for the Workforce

Preparing Students for the Workforce

There’s a line I hear every once in awhile from profs (mainly, but not exclusively, in the humanities) saying something to the effect of: their job is not to prepare students for the world of work; rather, they want to prepare students’ minds to be critical thinkers or better citizens, or something like that. Actually, it’s usually phrased less delicately, like: “I’m not preparing kids to be cannon fodder for the knowledge economy”; “I don’t give a damn what employers think, I only care about my students”, etc., etc.

Now, this is admirable, in a way. Universities certainly shouldn’t be training people for specific jobs (and to be fair, I don’t think there are that many people arguing this). Even where universities are offering professional education, as a rule they should be training people for diverse careers in a profession, not a particular job.

But in a way, it’s also kind of a silly position to take, for two reasons:

First: It’s not either/or. The insistence that education either has to be “for” the labour market or “for” personal betterment/critical thinking is laughable. For instance, most of the skills that matter for the humanities – the ability to critically appraise documents and arguments, appreciating complex chains of causation, writing clearly and effectively – are also pretty important in the world of work. Surely it is not beyond the wit of universities to design programs fit for multiple purposes. So why is there such a tendency within the academy to strut and preen and claim that never the two shall be one?

Second: If you really do want to put the student first, then employability skills need to be front and centre. Getting better jobs is really why students are there – and that’s been the case for a very long time.

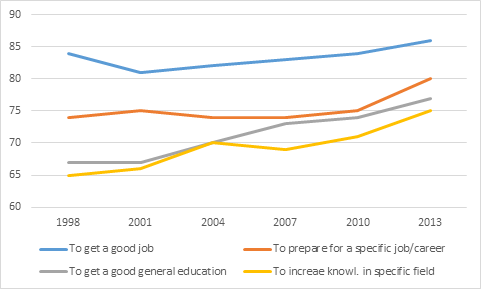

Every three years, since 1998, the Canadian Undergraduate Survey Consortium (CUSC) has been asking freshman why they decided to attend university. The top two answers have always been “to get a better job” or “to train for a specific job or career”. The next two answers have always been “to get a good general education” and “to gain knowledge in a certain field” (See? Students don’t think it’s either/or). The humanities aren’t exempt from this: 76% of students in these fields say “getting a good job” is “very important” to them.

Figure 1: Importance of Various Factors in First-Year Canadian Students’ Decision to Attend University, 1998-2013 (Percentage Indicating Each Factor is “Very Important”)

Now, if you actually drill down to what the single most important factor is, the results are even starker. In 2013, fully 68% picked “getting a good job” or “preparing for a career” as the most important reason to attend university; only 16% picked “increasing knowledge in a specific field” or “getting a good general education”. That’s not new, either: in 2001 it was 65% and 16%, respectively.

So while it’s legitimate to want to ignore the views of employers (especially in an era when employers are getting simultaneously pushier about wanting job-ready graduates, and stingier with the training dollars), it’s not legitimate to say that higher education shouldn’t be concerned with employability and the labour market.

It’s not for the companies – it’s for the students. It’s what they want. It’s what they think they’re paying for. It’s what they deserve.

0 Comments