CORE FUNDING VERSUS THE HUSTLE

CORE FUNDING VERSUS THE HUSTLE

| ALEX USHER

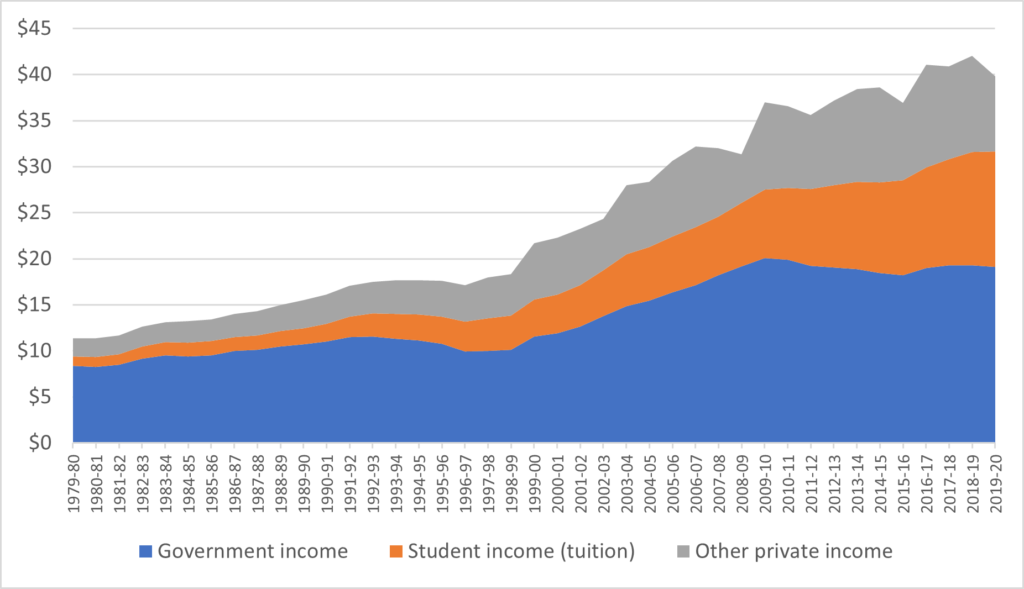

If you’re a long-time reader, you’ll know I often produce diagrams of funding trends for Canadian universities that look like this:

Figure 1: Total University Revenue by Source in Billions of $2019, Canada, 1979-80 to 2019-20

But I am starting to think this method of portraying the data does not actually explain what is going on in universities these days. Instead, I think there are really only two categories of funding that matter: those that involve getting paid for traditional university activities – i.e. teaching domestic students – and those that involve hustling for dollars in a competitive market.

Allow me to define these two categories a bit more.

Universities get a substantial chunk of their funding just for existing and teaching a certain number of students. This includes nearly all of the grants they receive from provincial governments, as well as the money they receive in tuition fees from domestic students. Now, I know that there is competition between institutions for domestic students, but it’s pretty limited. Most universities have in Canada have some kind of regional catchment area, either individually or as a duopoly, and in the latter competition is really about who gets the “best” students, not over total numbers. Some regional catchment areas – in particular those outside major metropolitan areas – are shrinking and so for institutions located in these areas, “predictable” funding might sometimes mean shrinking funding. But the point is, institutions have a pretty good idea year to year what their money is going to be from this source, and moreover, the money from these sources fund what you might call the “core” areas of the universities – that is, to academic departments for the purpose of staffing core positions. Call this potion of funding the “Traditional” dollars.

But then there are the areas where institutions and individual researchers need to hustle in order to generate revenue (and just to be clear: I am using “hustle” here in the sense of having to work hard in a competitive environment, rather than the sense of running a fraud or a swindle). That includes basically all of the federal revenue, which is distributed competitively either on an individual level (the tri-councils) or an institutional one (CFI, CFREF, etc). It includes all the money that comes in from donations, grants, contracts, and other forms of self-generated revenue. And, crucially, it includes money from international students. This money comes from competitive processes, and universities have to work a lot harder for it than they do for their traditional forms of revenue. Call all of these the “Hustle” dollars.

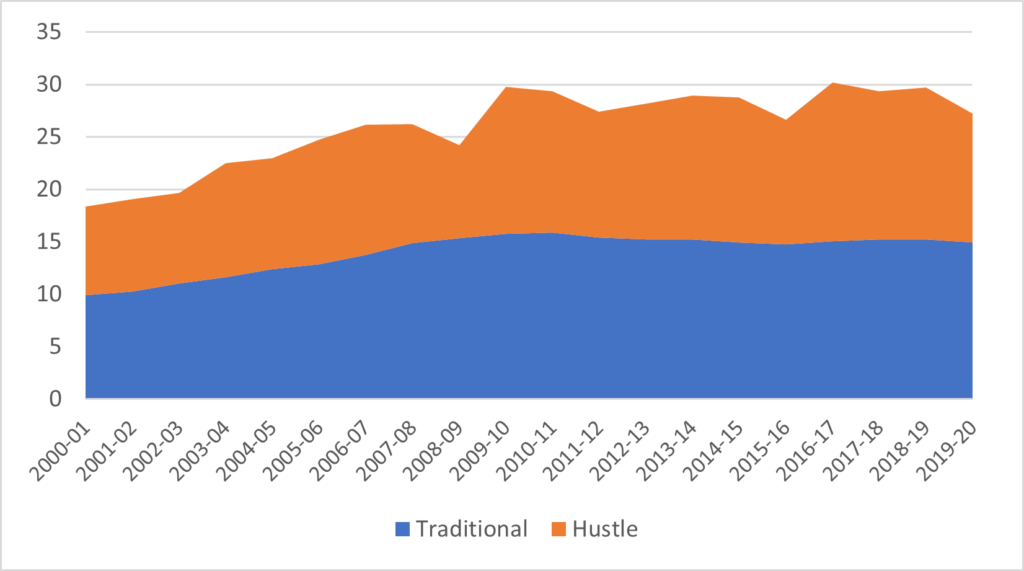

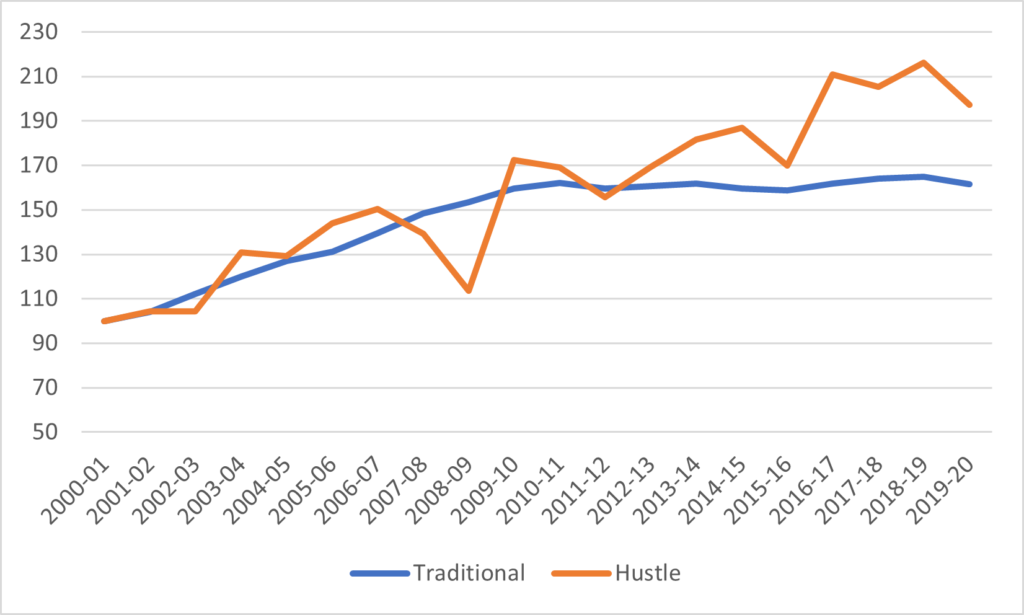

Now, look for a second at how these dollars have changed over time. Figure 2 shows the balance of traditional dollars to “hustle” dollars in university revenues, excluding student fees (which we’ll get to in a second), from2000-01 to 2019-20. “Traditional” dollars basically plateaued in 2009-10, while “Hustle” dollars have trended up slightly, though with a lot of year-on-year volatility, mainly because a good chunk of hustle money comes from returns on investments, which change substantially from year-to-year.

Figure 2: Total Institutional Revenues Minus Student Fees by Type of Revenue in Billions of $2019, Canada, 2000-01 to 2019-20

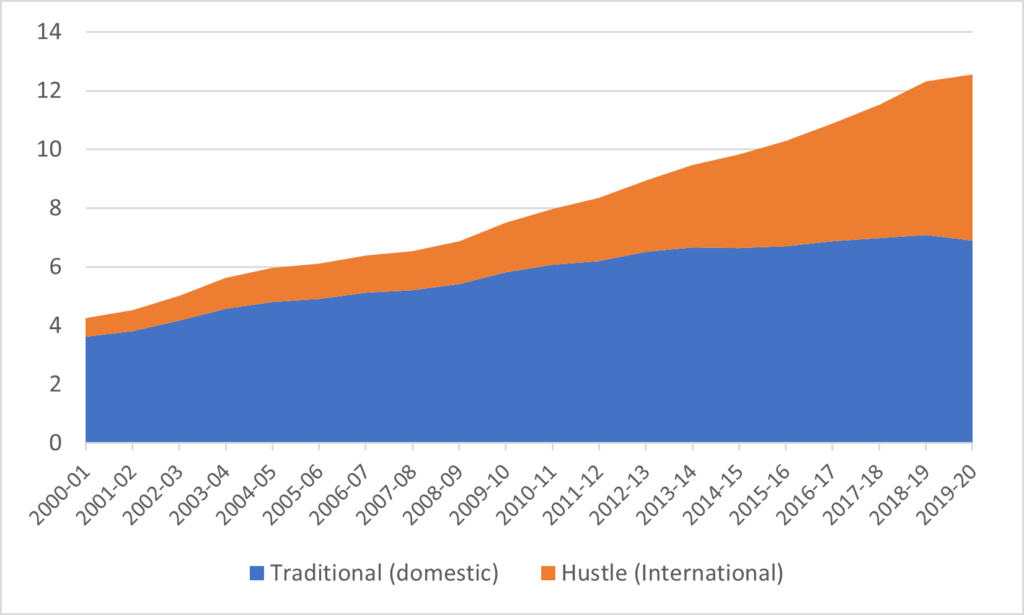

Now let’s take a look specifically at student fees, which is where the big action has been over the past 20 years. It is not just that fee revenues have tripled in real terms over the past two decades, it is that the share of fees coming from international students has tripled, from 15% to 45%. Basically, income from domestic (traditional) sources came to a standstill about eight years ago, while income from international (hustle) sources continued growing at a terrific rate. As of 2019-20, fee income from international students was approaching 45% of all university fee income. COVID will have reduced that a bit, but it seems likely that universities will be receiving over half their fees from international students before 2025.

Figure 3: Total Fee Revenue by Source in Billions of $2019, Canada, 2000-01 to 2019-20

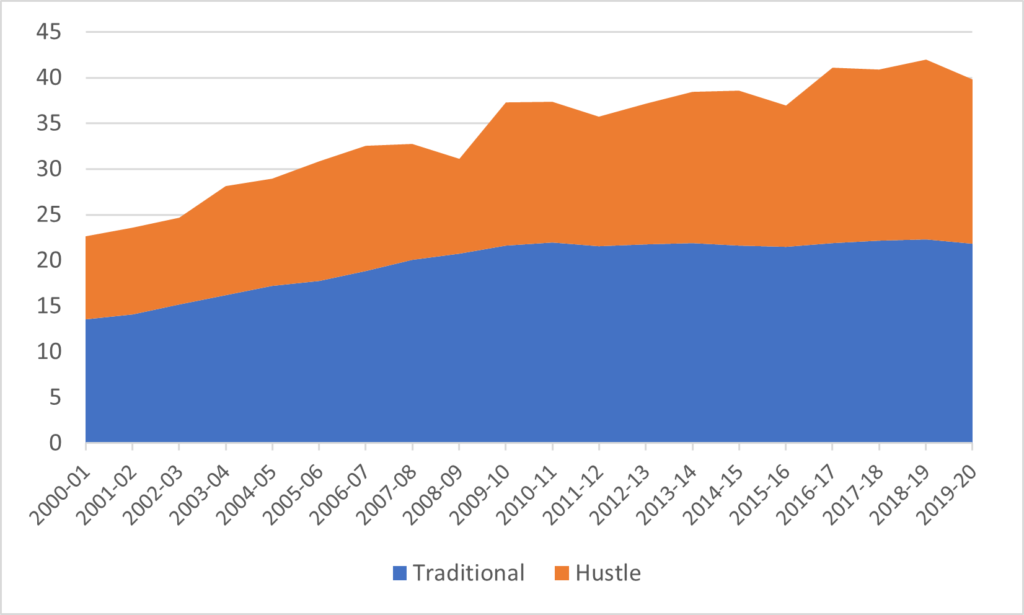

Now, if you put the data from Figure 2 and Figure 3 together you get Figure 4 (below). “Hustle” money isn’t quite outweighing Traditional sources of income yet, but it’s getting close; it’s now about 46% of total income, up from about 40% two decades ago.

Figure 4: Total Institutional Revenues by Type of Revenue in Billions of $2019, Canada, 2000-01 to 2019-20

Figure 5 displays the same data on a slightly different way. Basically, hustle and traditional money were increasing at roughly the same right until about 2012. Since that time, nearly all of the increase in university income has come from the “hustle” side rather than the traditional side.

Figure 5: Total Institutional Revenues by Type of Revenue, Canada, 2000-01 to 2019-20 (2000-01 = 100)

The shift in funding from traditional to “hustle” has real effects inside institutions. Traditional sources don’t require a lot of upkeep: as long as professors show up to teach classes, that money is going to keep flowing. But hustle money requires a lot of upkeep. You want to chase research dollars? That requires investments in laboratories, and in a whole infrastructure of research management. Want to chase donor or investment dollars? Prepare to spend big on an advancement office and/or investment advisors’ fees. Want to get international students? You’re going to need to spend money on agents and marketing. In short, chasing these dollars raise costs, and almost none of these costs end up on the academic side of the house. Unsurprisingly, this leads to noses being put out of joint: as in many organizations, power in higher education is seen to reside in those areas which are growing, and these days, very little of the growth is on the academic side.

Now, does that mean that this chasing for Hustle dollars is not worth it? It would be interesting to take a deep dive into institutional finances to see how much universities are spending to chase the hustle dollars and whether they are in fact getting a positive return. While there is almost certainly a positive return that is getting re-invested in the academic side, it might not be all that large (or at least not consistently large across all institutions) once you subtract all the costs of acquiring these revenue streams

But given the long-term stagnation in traditional funds, the lure of extra money, no matter how small, has a very powerful effect on universities. Even if the hustle is an exhausting treadmill, I can’t see many (any?) institutions volunteering to step off.

0 Comments