FALL 2020 INTERNATIONAL ROUND-UP: NETHERLANDS

FALL 2020 INTERNATIONAL ROUND-UP: NETHERLANDS

| ALEX USHER

Here’s a headline you don’t see every day: “Dutch aim to Stop Academics Working at Weekends”. I hope Times Higher Education won’t mind me filching the opening paragraph, which is something: Academics should not be forced to squeeze their research into weekends and holidays, according to the Dutch education minister, who admitted that pressure on some researchers had become intolerable and that professional competition had gone “too far”.

Well, now. What to make of this?

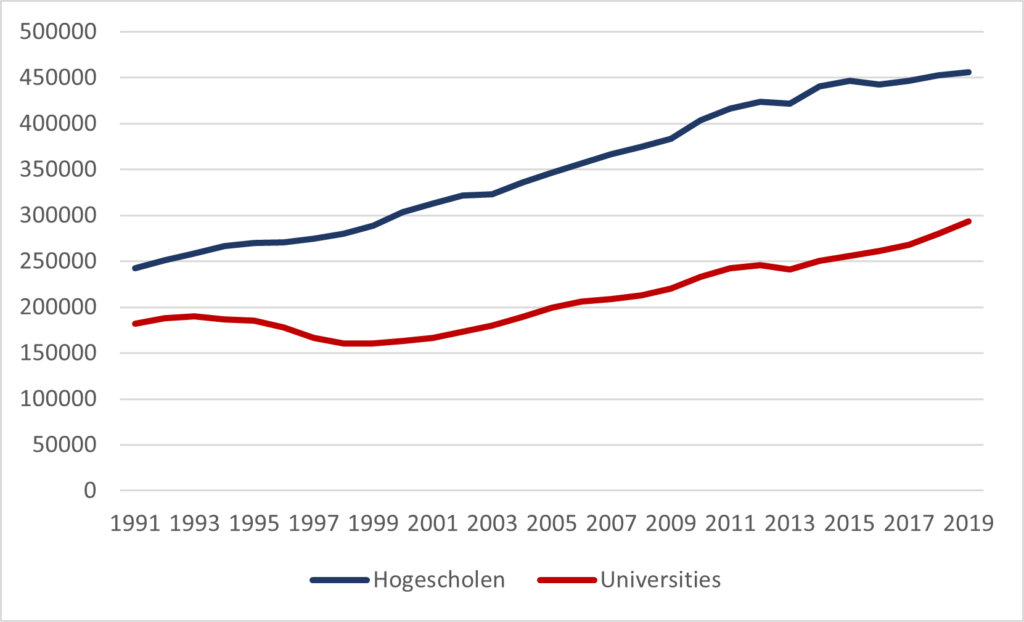

Let’s start with a refresher on Dutch higher education. At a high level, the system resembles Germany’s: a set of universities on the one hand, and a highly developed set of degree-granting non-universities (Fachhochschulen in Germany and Hogescholen, or HBO, in the Netherlands). Think of the HBOs as being like Canadian polytechnics, but on steroids – basically everything they do is what we would call “applied degrees”. What makes the Dutch system remarkable is that it puts 60-65% of all its students graduate through these HBOs, leaving the universities to teach about a third of all school-leavers.

Until recently, the HBOs have sucked up most of the increased demand for higher education, meaning universities focused on what universities love to focus on: research. The country has 13 universities, and 12 of them make the world’s top 500 in the Shanghai Rankings, 9 make the top 200 and 4 make the top 100. There’s basically no other university system in the world quite as research-intensive from top to bottom. It’s quite an accomplishment for such a small country.

The thing is, strains are building. The Dutch government, after a couple of decades of funnelling demand into HBOs, switched tracks about a decade ago and started funnelling students into universities instead. Absent a lot of new resources, that makes it harder to keep up a high research pace.

Figure 1: Enrollments in Netherlands Higher Education Institutions by Sector, 1991-2019

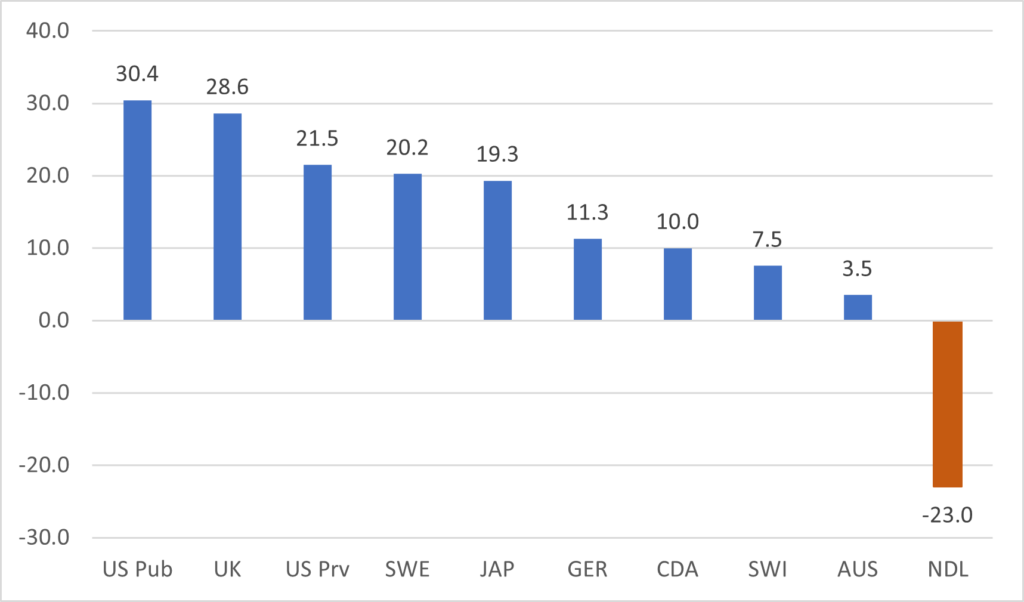

Not to put too fine a point on it, few governments have done less than the Dutch in terms of providing new resources. Despite Dutch institutions being absolute wizards when it comes to attracting research dollars (in particular, ones coming from European Union research funds), the fact is that Dutch universities are having to do with a lot fewer resources than before. That they have managed to stay on top of the research league tables as long as they have is probably due to an enormous amount of unpaid overtime by professors (something which has led to hundreds of complaints to a national labour body over the past few years.)

Figure 2: Percentage Change in Real Expenditures per Student, Top-200 Universities, by Country, 2006-2017

It seems like something snapped. In 2018, the Association of Universities of the Netherlands announced an intention to move away from promotion based on research metrics and towards a recognition of teaching achievements. Late last year, the Association released a paper entitled Room for Everyone’s Talent: towards a new balance in the recognition and reward of academics, which committed universities to a large-scale re-drafting of job descriptions, in particular creating new recognition and rewards systems within institutions to recognize achievements outside the research realm. I don’t know the background here, but it seems reasonable to infer that universities themselves, tired of the research rat race, decided to try changing the very definition of what it meant to be a academic.

This is the context for last week’s provocative headline: the government is now getting on a bandwagon the universities themselves have created. If it is no longer possible to do more with less, then perhaps it is time to understand how to do less with less. Kudos to the Dutch for having the courage to admit this. It will be interesting to see how this translates to other countries that find themselves particularly overstretched in this area (Australia is the next obvious country to find itself in this bind, particularly with the budget carnage that COVID is producing, but Canada isn’t that far behind).

The question here is whether faculty will actually want to stop working at weekends. I mean, it seems like a good idea in theory, but it seems to me that there are two things standing in the way of this working in practice. The first is that even if the Dutch academic rewards system stops rewarding research so much, it’s not clear how much impact that will have on Dutch academics as long as the prestige system in the rest of the world continues to value it. Academia, for better or worse, is global, as is the prestige system that goes along with it. Can any national system stand against the global tide and say “halt”? We’ll see.

But the other reason is simply that academia – how can I put this? – attracts a lot of type-A personalities. Both the government and the Association of Universities seem to think it’s possible to use official forms of recognition (pay, promotion) as a way to get profs to not work so hard. But the intrinsic code of academia is respect of colleagues, which in turn is based on research output. Maybe that’s worth a few weekends, just to get ahead of one’s colleagues. But if the colleagues respond – as game theory might well suggest they do – by increasing their hours to keep pace, is there anything a government edict can do to stop them?

All in all, an interesting experiment, one well worth watching and learning from.

0 Comments