Has the online transition worked out? How far are student numbers likely to decline? Will governments still have money to invest in universities and research after the pandemic is over? And what does all that mean for staffing? These are just some of the issues explored by our survey of 200 university leaders from 53 territories. Paul Jump runs through the results

How badly – if at all – are their institutions’ finances likely to be hit by a crisis distinguished by the unpredictability of its duration and the variability of its consequences? Should they go all in with online education, on the assumption that blended learning will become the new normal? Or do they bank on silicon natives still preferring to be taught in carbon-centred environments? Should they assume that international students will still value the intercultural experience of studying abroad, or plan for much less cosmopolitan and more socially distanced campuses? And is there a way to remain financially viable in all these scenarios, or are some institutional bankruptcies inevitable?

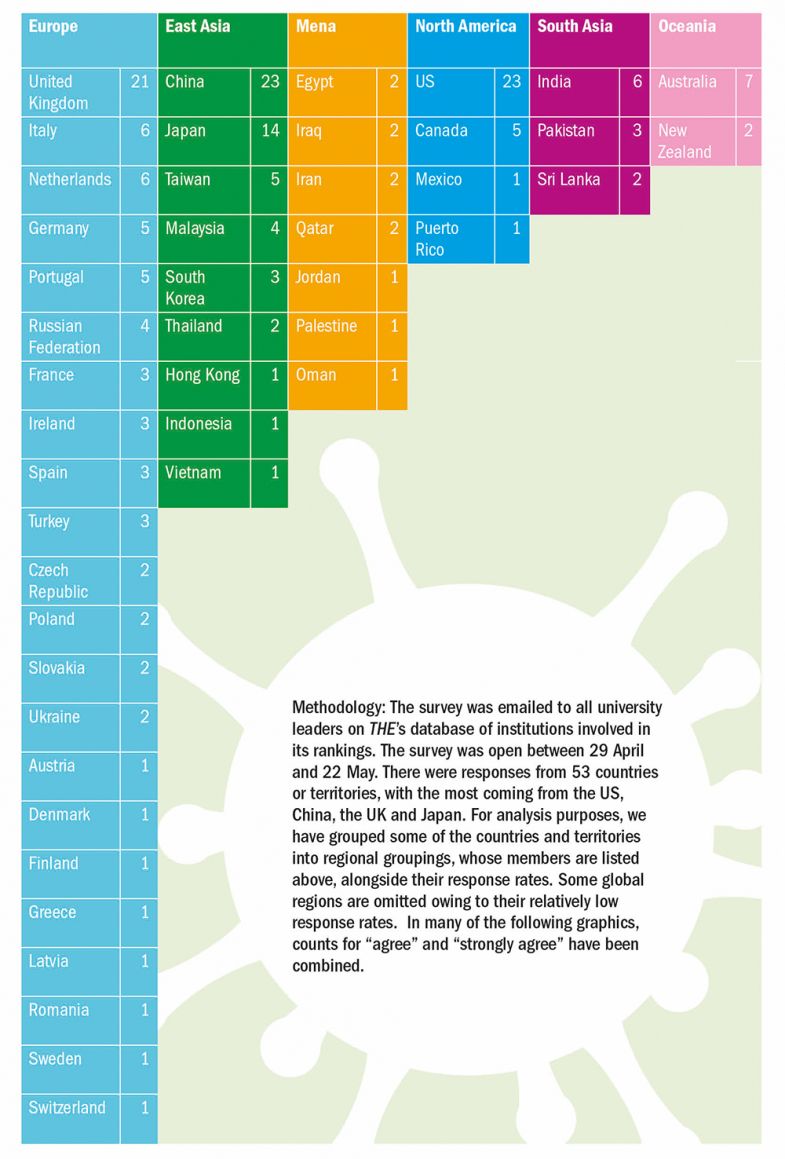

These are the kinds of issues that Times Higher Education has sought to explore with our latest global survey of university leaders, focused on the Covid-19 pandemic. During the first three weeks of May, we surveyed 200 leaders of prestigious universities around the world. The results – from 53 countries or territories, across six continents – paint a picture of a sector whose chief concerns inevitably vary by region and system, but that is united in seeing the coronavirus pandemic as a potentially game-changing event in the modern history of higher education.

Click here to see full results of survey

The online switch

Quite apart from the longer-term considerations, the sudden lockdowns enforced across the world by the pandemic have thrown up a host of issues requiring urgent resolution. Most salient among them is how to keep teaching when all your staff and students are confined to their homes.

All but 11 of the 200 respondents to the survey, carried out in collaboration with Microsoft, reacted by moving at least a quarter of their teaching online, and more than half moved all of it. Even institutions that have maintained some in-person teaching have had to tailor it according to social distancing requirements. For instance, in Taiwan – which has had fewer than 500 cases of Covid-19 and only a handful of deaths – National Tsing Hua University has moved classes with more than 40 students online, according to its president, Hong Hocheng. Arrangements for smaller classes have been left to individual teachers’ discretion.

Most respondents are content with the way they have handled the online switch. A full 85 per cent believe that their transition has been successful from a technical point of view. For instance, Sarah Springman, rector of ETH Zurich, reports a “stunning response from colleagues” to the need to teach more than 1,200 courses online during the summer semester. Only about 10 had to be cancelled “because the lecturers were external – and these were all small and optional courses”. Some lab courses have also been run with “very creative solutions and virtual labs to reduce the number that will have to be caught up on once students can access campus again”, Springman says.

All this despite the fact that planning at ETH Zurich only began at the end of February for a transition that took place on 16 March and incorporated feedback from study directors, student leaders and department heads. As well as Zoom teaching from home, the institution offered 300 priority classes the opportunity to do their teaching from lecture rooms on campus: an option that was “highly appreciated by those who still like to use the blackboard”, according to Springman.

Asked what they believe they have done particularly well, many respondents cite the technical support they have offered to help lecturers make the online transition. According to a UK vice-chancellor, “behind-the-scenes learning technical support has been critical in ensuring that academic colleagues feel confident to experiment and develop further than before. Moving learning that requires laboratory and simulation-type work has been a challenge [but] we have some examples where we have done this well.”

Thailand’s prestigious Sasin School of Management also offered training and encouraged experimentation. Some academics “leapt at the idea and bought their own additional equipment” such as microphones, according to the school’s director, Ian Fenwick. However, “a few simply didn’t want to try: better not make them!”

How has the online switch gone?

Meanwhile, the Netherlands’ Wittenborg University of Applied Sciences set up an around-the-clock helpdesk to answer “every conceivable question” from its 1,200 students and staff, who hail from more than 120 different countries, according to its president, Peter Birdsall. Answers are provided “even if it means forwarding the question to a teacher, a supervisor, a tutor, a registrar, a visa expert, the housing team or a technical person. Keep support centralised and coordinated – that’s a proven success.”

Universities that have not moved all their teaching online commonly cite a concern that their students lack access to the facilities necessary to profit from it, such as computers, broadband and quiet work environments. However, some have attempted to address this deficit, too; a university in South Africa, for instance, has ensured that “students from low socio-economic backgrounds are provided with hardware and data so that they can get on with the work”.

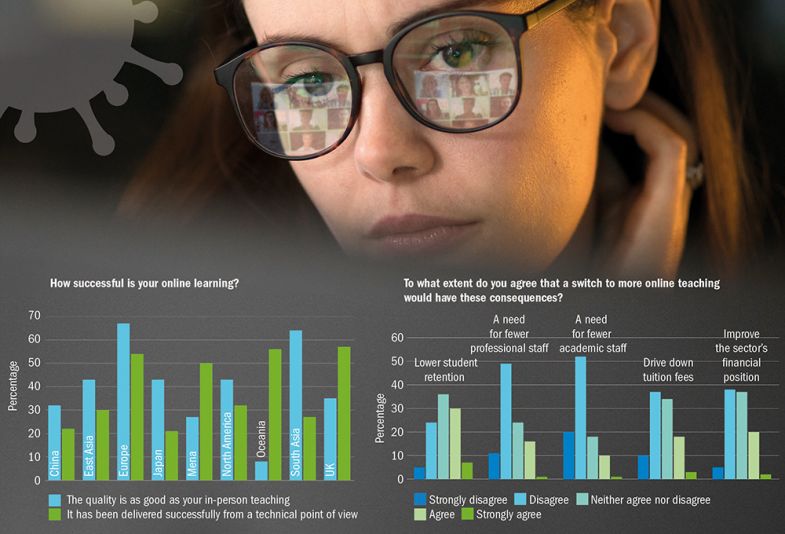

Respondents are also largely convinced that their virtual teaching bears comparison with their in-person teaching. While 20 per cent of respondents believe that quality has suffered as teaching has moved online, 40 per cent disagree.

However, there are regional variations. While confidence about the technical success of their online transitions is particularly high among leaders in Oceania (Australia and New Zealand), Mena (Middle East and North Africa) and Europe (including the UK), those in the first two regions are much less sure that the quality of their online teaching is as good as that of their in-person teaching (although the biggest response in both regions is that it is too early to judge). Just 8 per cent of respondents from Oceania (all but two of which are from Australian institutions) believe this to be the case, compared with 67 per cent of respondents in Europe and 64 per cent in South Asia. An Australian vice-chancellor notes that while their institution’s teaching has been “very high quality in difficult circumstances, it is not possible to flip to online learning so quickly and maintain the same degree of quality as either face-to-face classes or courses designed to be taught online”.

Moreover, several respondents make the point that while their online teaching may be as good as their offline teaching, the same cannot be said for their wider online student experience. Efforts have certainly been made to offer more than teaching online: a Chinese university, for instance, provides real-time online counselling and guidance via seven different communication platforms, such as WeChat and Dingding, and a UK institution offers a “virtual cafe with access for all students and small email study groups”, as well as “a series of short inspirational videos and articles, home grown and from the internet”. However, another UK vice-chancellor confesses that “the campus environment that helps to provide an excellent student experience is missing”.

A number of respondents also stress that the ease with which in-person teaching can be transferred online varies considerably according to discipline. Social sciences, business and computer science are often cited as having found the transition easiest, while courses with practical elements and assessments are typically seen as having found it hardest, especially medicine and dentistry.

But other respondents believe that the issue is more one of disciplinary attitude. One UK vice-chancellor says that “courses that lead to professional qualifications and [that] are taught by academics of the same background will have retained a hugely professional and positive approach to going online, regardless of how easy or otherwise it is. Others do not have that behaviour or attitude and therefore make it more difficult.” A US leader agrees: the problem comes with departments that are “stubborn and tradition-bound. They will have to be forced to change.”

Student assessment and teaching quality

Assessment

Of course, university leaders’ perceptions of how successful their online transitions have been do not necessarily bear a close relation to how their students see it. Course evaluation questionnaires are the traditional means of determining student perspectives, but some commentators have suggested that they ought not to be carried out this year for courses forced online. THE’s survey was carried out before many online courses had ended, but 79 per cent of respondents were planning to use them for all such courses, and another 17 per cent would decide on a course-by-course basis.

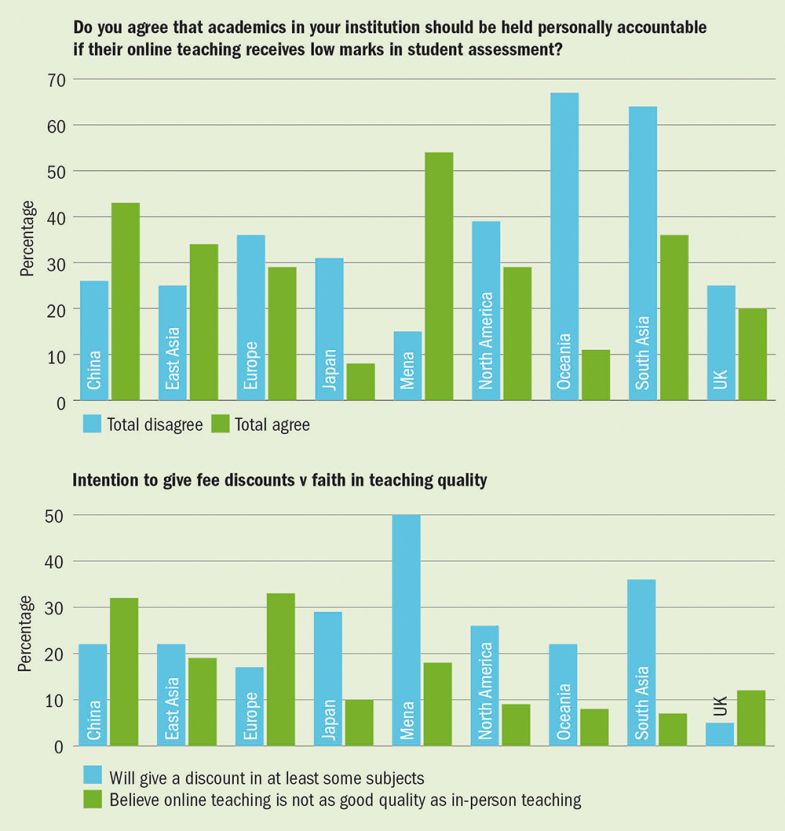

Opinions were more mixed, however, about whether academics should be held personally accountable if their online teaching receives low marks: 31 per cent thought that it was fair to do so, while 33 per cent thought that it was not, with very few having strong views either way.

Some respondents object to the whole concept of holding individuals to account for poor teaching scores. The leader of a Swedish university argues that “low marks in student assessment should almost never be held against individual academics. Course evaluation surveys are a tool for monitoring course quality, not teacher quality.”

But most disagree. According to Nick Braisby, vice-chancellor of the UK’s Bucks New University, the issue “needs to be handled sensitively, but academics do have a responsibility to deliver high quality even as they are challenged to master a new mode of teaching”. That view is echoed by Jay Stowsky, senior assistant dean for instruction at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business – but with the caveat that academics “can’t be held responsible for the overall shift to remote instruction, just for doing their very best to deliver instruction in this modality”.

Another UK leader thinks it is better for staff to be held accountable for “engaging well” with institutional training on online delivery: “We have revamped many of our assessments for students to reflect the online nature of the assessment [but] there are many factors affecting student assessment, of which academic learning is only one, [so] we will be looking at all factors, not just one.”

On the other side, Chandrika Wijeyaratne, vice-chancellor of Sri Lanka’s University of Colombo, says it is “far too premature to assess quality of teaching for a population of teachers who were not familiar with digital education…If the format of student assessment has also undergone a major change, we cannot attribute it to poor quality teaching alone.”

But how long such latitude will be extended is open to question. A US university leader believes that for the first online semester, staff shouldn’t be held accountable for the quality of their teaching “because they weren’t prepared for the transition. Some have done extraordinarily well and others have been marginally effective. Next semester, they all need to get it right.”

One question raised by all this is whether students should be compensated for the potential disruption to their learning caused by the shift to online teaching. Just 12 per cent of THE’s respondents intend to offer compensation in all disciplines, and another 11 per cent aim to offer it in some, compared with 49 per cent who do not. There are wide regional variations however, with 50 per cent of Mena universities intending to give a discount, compared with just 5 per cent of UK respondents. Interestingly, there appears to be no significant correlation between regional intention to give a discount and perceptions that online teaching is not as good as in-person teaching.

Some institutions deny that any disruption has been caused by the online transition, and many point out that their tuition is free anyway – at least to domestic students. But others recognise that some of their students have faced particular difficulties. For instance, Australia halted immigration from China “relatively early”, according to one Australian vice-chancellor, meaning that international students who were stranded in China “had a restricted choice of units of study to choose from, which means that these students will need to undertake an additional semester. As a consequence, this discrete group of students are able to apply for compensation per unit of study, up to a fixed amount.”

Another Australian university has given a discount to all international students for the second trimester “to recognise the financial difficulties that many of them are in”. Bahçeşehir University in Turkey is offering all students the right to suspend their education during the pandemic without incurring any extra charges. And the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico (UAEM) is offering full discounts to students with the lowest incomes and who are most affected by the economic fallout of Covid-19.

What about assessment of students? A key question has been whether and how to conduct online exams. Most universities in our survey are doing so, 44 per cent for all courses and 43 per cent for at least some. But some institutions are requiring students to do the exams in front of their webcam for invigilation purposes. A UK university is also using “random verbal exams to ensure fairness/lack of cheating” – but will still use the online exam results of final-year students only to “assist in final marking”.

An Australian university is only using online exams “for those courses where it is a requirement for accreditation by a professional body” while the leader of another sees the Covid crisis as an opportune moment to “de-emphasise exams as the main mode of assessment in many programmes”. They also worry that “access to quality online proctoring services at scale is limited”.

But if online exams are not the best option, what is? THE’s respondents plump overwhelmingly for continuous assessment. Other suggestions include projects and e-portfolios, perhaps accompanied by an oral exam, while some leaders advocate a horses-for-courses approach. “We have to trust the wisdom, expertise, and compassion of our faculty members in an extraordinary situation,” according to one US leader.

Meanwhile, one university is continuing with in-person exams, but “with groups of three students as a maximum” and with procedures to thoroughly clean exam rooms between each sitting.

Finances and international students: the effects of Covid-19

Student recruitment

Looking ahead to the next academic year, admissions processes will also have to adapt to the fallout from the coronavirus. In many countries, end-of-school exams have been cancelled or carried out in very different ways from other years; in the UK, for instance, A-level grades will be based on teachers’ assessment of likely scores.

Nevertheless, 68 per cent of respondents to our survey have decided to stick to their standard admissions timetable, against 10 per cent who definitely won’t. And 67 per cent of respondents agree or strongly agree that their admissions process this year will remain as rigorous as it normally is, against only 9 per cent who disagree.

There are caveats, however. Some universities have delayed the start of semesters and/or extended application deadlines. And Shoichiro Iwakiri, president of Japan’s International Christian University, concedes that while his institution’s admissions process will be rigorous, it will have to take into account that high schools “won’t be able to submit results of exams and evaluations, [so] the sense of ‘rigour’ will change.”

But how many students will actually apply this year, given the likelihood – already confirmed by many institutions – that their teaching, if not their tutorials, will have to be carried out online until a vaccine is found? According to one UK survey, by London Economics for the University and College Union, domestic undergraduates due to begin their courses in October are 17 per cent more likely to defer the beginning of their higher education as a result of the pandemic. An earlier report by the same organisations estimated that there will be a 47 per cent decrease in the UK’s international student enrolment in the next academic year, costing the sector a combined £1.5 billion.

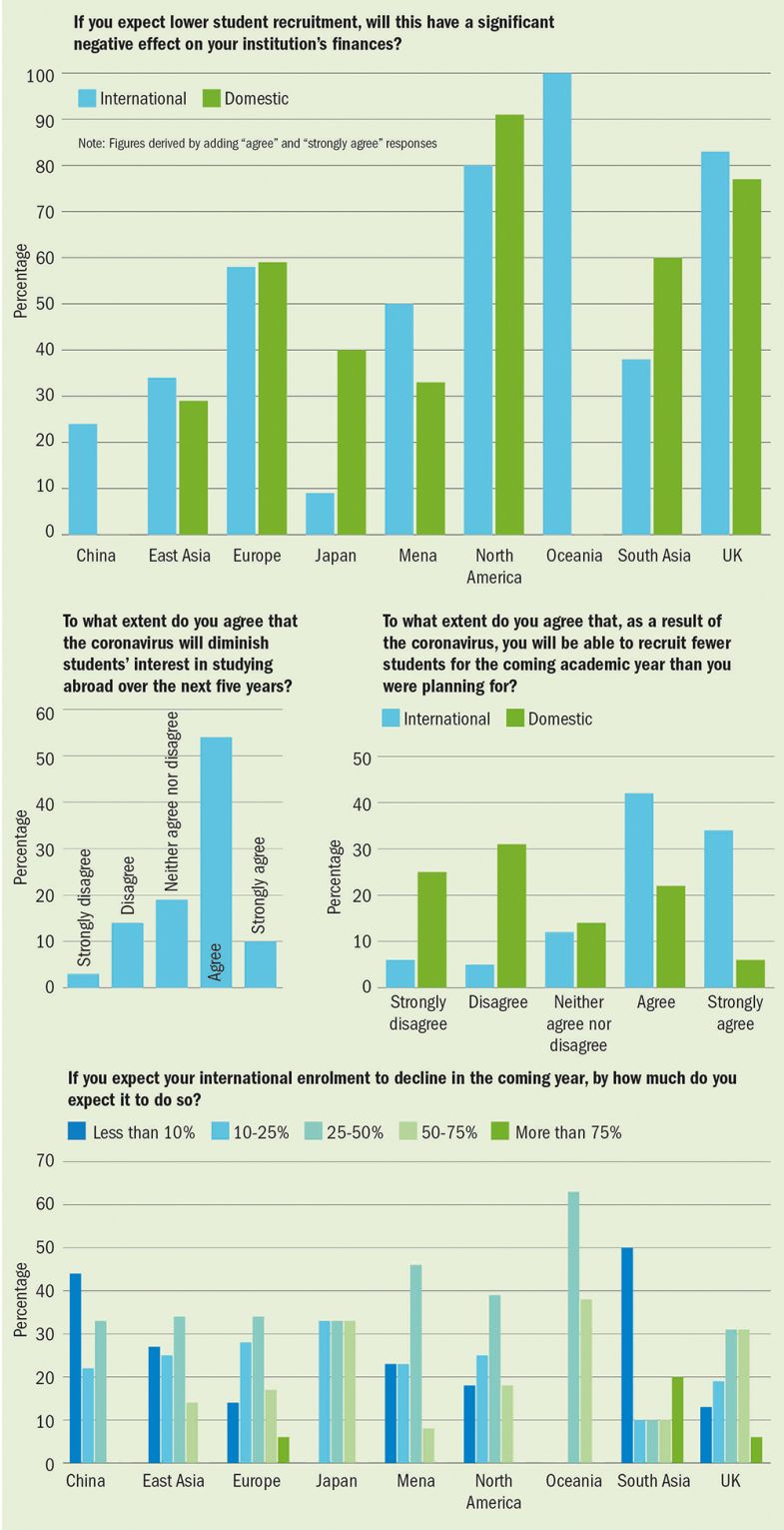

Overall, 76 per cent of THE’s respondents expect to be able to recruit fewer international students for the coming academic year than they were originally planning for. Not surprisingly, that conviction is strongest in systems that recruit the most international students. All respondents from Oceania expect international recruitment to fall by between 25 and 75 per cent in the coming academic year – even though one vice-chancellor notes that “our applications from international students are currently up over 20 per cent on this time last year”. And 93 per cent of leaders in North America and 78 per cent of those in South Asia also expect declines in international recruitment – although their projections of how much it will decline by are less pessimistic.

A very high proportion of European universities also expect declines. “The problem is related to closed borders,” explains Michal Lostak, vice-rector for international relations at the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague. “We have now 38 per cent of our applicants from abroad but if they cannot get visas due to locked embassies there will be a problem.”

The Wittenborg University of Applied Sciences’ Birdsall also agrees that more students, especially in East Asia, “will stay closer to home. However, we believe that ‘career mobility’ – study in a wealthy European country [with post-study work opportunities] – will remain a driver for countries such as The Netherlands.”

The Netherlands has been more focused on international students than most countries on the European mainland but its financial reliance on them is still much lower than that of the anglophone countries. In general, European universities’ expectations of how hard a decline in international students would hit their finances is lower than those of the anglophone nations. For instance, at ETH Zurich, “all of our students pay the same fees. We do not rely on foreign students to fund our educational model,” notes Springman.

Indeed, some institutions take an entirely non-financial approach to international students. Many Mexican universities, for instance, give international students financial support “to improve their stay in our country”, according to UAEM’s rector, Alfredo Barrera-Baca. Nigeria’s Alex Ekwyeme Federal University, Ndufu-Alike also offers “low tuition to international students: hence our expectation to admit more in the next academic session”, says its vice-chancellor, Chinedum Nwajiuba.

Some institutions have begun to react to the expectation of lower international admissions by planning for more online teaching. The Polytechnic University of Milan, for instance, “has already decided to carry out teaching in blended mode. This will limit the decline of international students to 10 to 15 per cent at most,” predicts the institution’s rector, Ferruccio Resta.

The recruitment of domestic students is less of a concern. In all regions, the number of respondents expecting to recruit fewer domestic students is lower than the number expecting fewer international students. In Oceania, for instance, none do. One Australian vice-chancellor predicts two reasons for a domestic “surge” between 2021 and 2026: “a demographic one, as a result of domestic birth rates 20 years ago (which adds 4 per cent over the cycle), and increased demand during a recession (adding another 4 per cent?).”

However, in South Asia, Japan and North America, concern about the financial implications of a decline in domestic admissions is higher than concern about the impact of international recruitment declines, and in Europe and East Asia, concern is at similar levels.

“My institution is reliant on undergraduate home recruitment,” notes one UK vice-chancellor, adding that the government’s 5 per cent cap on growing domestic admissions this year will “make the home market even more competitive, which is likely to disadvantage my institution”.

Even if there is a sharp downturn in income from tuition fees in the short term, a key question is how quickly – if at all – student numbers will recover.

Overall, 64 per cent of respondents agree that the coronavirus will diminish students’ interest in studying abroad over the next five years, against 17 per cent who disagree. Again, pessimism is highest in Oceania and North America, as well as Mena (the only region where concern about the next five years outstrips concern about the next year). UK vice-chancellors appear more upbeat, although more than half still expect diminished student interest in studying abroad over the next five years.

A sense that student emigration will be reduced post coronavirus is prevalent in one major source of outward-bound students: South Asia. An Indian leader predicts that “the major current destinations treated international students rather poorly”, and that the coronavirus “might lead to second thoughts about going to certain countries for higher education”. S Sadagopan, director of the Indian Institute of Technology Bangalore, also foresees “reduced student migration”, while Colombo’s Wijeyaratne suggests that Sri Lanka “may benefit from a reverse flow of our intellectuals, who had state-funded education and were lost to the richer nations. The silver lining of the pandemic is that we may have a brain gain.”

How will investment in science and research be affected?

Government support

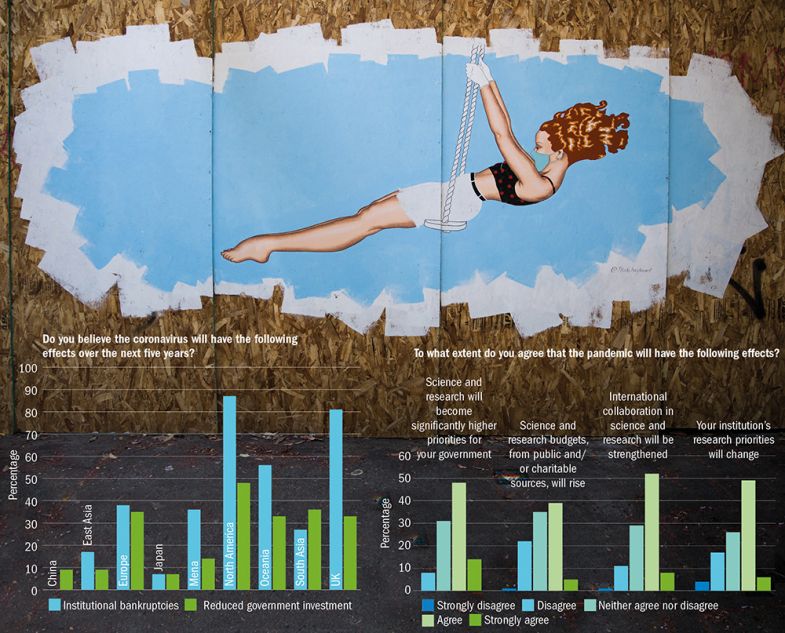

Another key variable in universities’ scenario planning is whether the financial hits that national governments have taken in supporting their economies during lockdowns will translate into a reduced willingness – or ability – to invest in research and higher education. Respondents remain relatively optimistic; only 28 per cent agree that the coronavirus will reduce governments’ willingness to invest in higher education over the next five years, against 45 per cent who do not. Confidence is highest in East Asia, where just 9 per cent of respondents expect government investment to fall, against 64 per cent (and 78 per cent in China) who do not.

But respondents in Europe and South Asia are roughly evenly divided on the issue, while more North American leaders (48 per cent) expect a decline than do not (19 per cent): “[The politicians] were already divesting. This trend will simply continue,” says one US college president.

“Governments around the world will seek to drive down the level of funding per student,” adds an Australian vice-chancellor. And a Chilean leader suggests that the question is not so much political willingness as the fact that, given all the economic damage wrought by the virus, governments will have “other priorities”. UAEM’s Barrera-Baca counters that the virus has illustrated the importance of professionals in every sector. Hence, their preparation for professional life “is a responsibility of the government of each country, so investment in higher education should be even more of a priority”.

If state investment does decline – or even if it fails to increase in line with the loss of income from international students – some observers fear that some universities may go bankrupt. Overall, 42 per cent of respondents expect the pandemic to cause institutional bankruptcies in their country, but that figure masks huge regional variations. While 81 per cent of respondents in the UK and 87 per cent of those in North America expect this, most other regions disagree. Most confident, once again, is East Asia, where just 17 per cent of respondents expect bankruptcies.

The only other region with significant fears of bankruptcies is another marketised system: Oceania. But, according to one Australian vice-chancellor, it is still too early to tell: “There isn’t that risk in 2020 but there will be if the impact of this is compounded over the next three years.”

But no one expects closures to be widespread. Even in North America, 85 per cent of respondents who predict bankruptcies expect less than 25 per cent of the sector to be affected. Conversely, while Japanese leaders are generally sanguine, those that are not are particularly gloomy: of the six out of 14 leaders who expect bankruptcies, half expect more than 25 per cent of the Japanese sector to be affected.

Redundancies, furlough and pay cuts

Staffing

Even if most universities remain solvent, one major concern arising from the economic impact of the coronavirus revolves around staffing. If university finances are hit significantly, will institutions respond by downsizing?

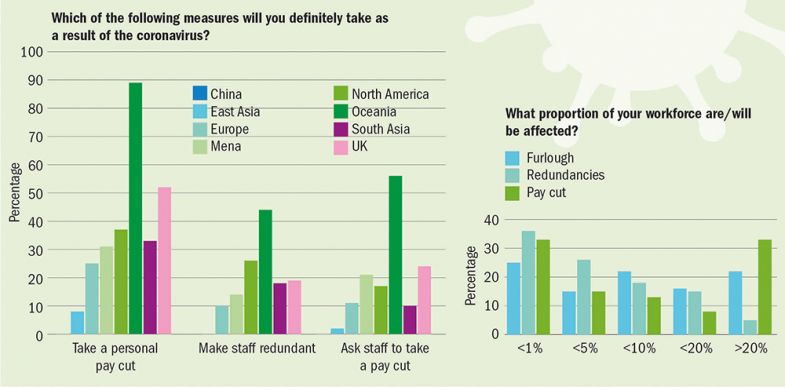

Some national governments are offering furlough schemes whereby staff members are put on temporary paid leave at public expense, the aim being to minimise job losses, at least in the short term. Nearly a fifth of respondents have taken advantage of such schemes, with a similar proportion considering it. For instance, almost all non-teaching staff at Lewis & Clark College in the US have been furloughed “for 20-40 per cent of their time during May, June and July”, according to the institution’s president, Wim Wiewel, while “faculty are already not on contract during June and July”.

However, 62 per cent of respondents have put less than 10 per cent of their staff on furlough, and most have applied it primarily to professional rather than academic staff. Other respondents note either that their country does not have such a scheme or that, as in Australia, it is not open to university staff.

A particular concern of early career researchers is that those of them on fixed-term contracts may be most vulnerable, either by having their contracts terminated early or by being denied an expected renewal. Among our respondents, 51 per cent do not expect to target those on fixed-term contracts: “If anything, we will extend [contracts], says ETH Zurich’s Springman. But 18 per cent firmly expect to do so. Indeed, some institutions are going further: Centurion University, a private university in Odisha, India, is “moving all non-statutory positions to five-year contracts, with a renewal option every year”, says its president, Mukti Mishra. And another 24 per cent of respondents are considering ending contracts early. One UK vice-chancellor, for instance, hopes it will not be necessary, but “we also have to find a way to manage extremely challenging financial realities”.

Nor are permanent positions necessarily safe. Asked if they plan to make any permanent staff redundant as a result of the coronavirus within the next six months, 12 per cent of respondents say they do, while 25 per cent say it is too early to say – but 59 per cent have no such plans. By far the most likely region to be predicting job cuts is Oceania, where 44 per cent of respondents are planning them. By contrast, no universities in East Asia have such plans.

Similar proportions of respondents plan to ask staff to take pay cuts, with a similar regional breakdown. In some countries, though, salary levels are not within institutional leaders’ discretion, while certain governments have made clear their own views on the matter; for instance, Russia’s State University of Management “follows the Ministry of Education and Science’s recommendation not to decrease payments for academics”, according to its rector, Ivan Lobanov.

Interestingly, in all regions, university leaders themselves are more likely to have taken a pay cut than to have asked their staff to do so. Nearly a quarter of respondents have taken or plan to take a personal pay cut, with the likelihood highest in Oceania (89 per cent), followed by the UK (52 per cent) and North America (37 per cent). By contrast, only 8 per cent of leaders in East Asia plan to take pay cuts, and none of the 23 Chinese respondents – possibly reflecting lower levels of concern about the financial impact of the coronavirus in that region.

European university leaders are also relatively unlikely to be taking a pay cut. ETH Zurich’s Springman notes that, unlike in some countries, Swiss university leaders “are paid [only] a very small differential above the vast majority of our full professors”. Other leaders are forgoing pay rises. For instance, Bucks New’s Braisby “will not be taking a pay rise, even though a substantial rise was recommended by my remuneration committee to give better parity to the market”.

UAEM’s Barrera-Baca has taken a 16 per cent cut, and is also making charitable donations to help vulnerable sectors, such as food kitchens. But by far the biggest sacrifice has been made by Centurion’s Mishra, who has taken a 100 per cent pay cut until September. His only income during this period is from consulting work carried out in his spare time.

“I can fall back on my small savings, which can sustain me for six months,” he says. “Beyond that, we will see.”

Does online learning now have wings?

Is online forever?

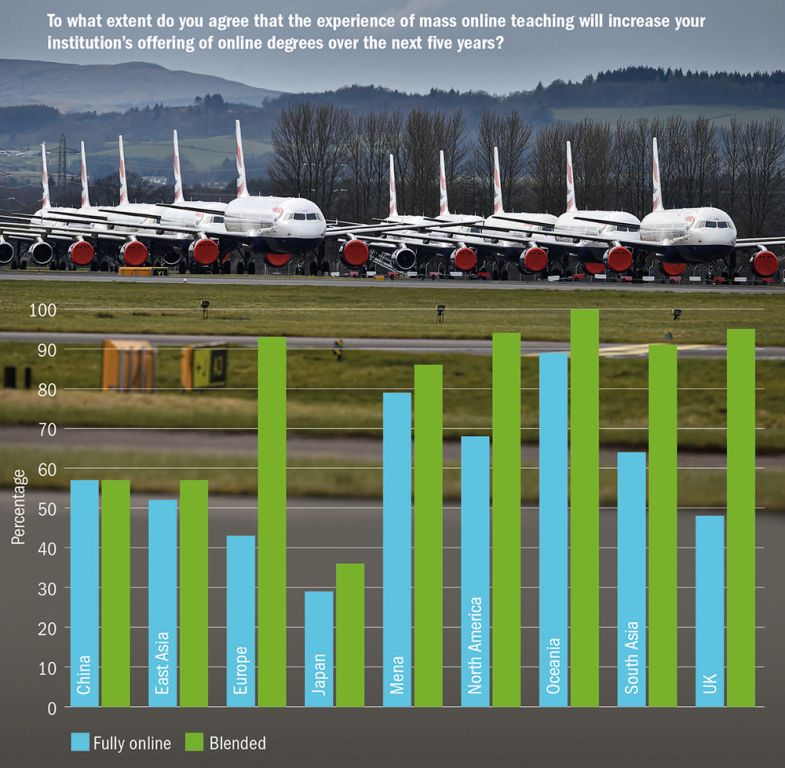

If international student numbers do decline, one obvious remedy might be to parlay the current online switch into permanent arrangements. Just under half of respondents who expect international student numbers to decline over the next five years say that they plan to respond by offering more fully online degrees to cater to the international student market, with enthusiasm particularly strong in Oceania, South Asia and Mena. In Japan, however, just 15 per cent of respondents intend to adopt this course. The country is also the least concerned about a decline in student numbers over the next five years; only 36 per cent of Japanese respondents have this expectation.

Regardless of concerns about the international student market, 55 per cent of respondents overall expect to adopt more fully online degrees, peaking at 89 per cent in Oceania. And 85 per cent expect to adopt more remote working. It looks like Zoom meetings may be here to stay.

More blended learning is also anticipated. For instance, Berkeley’s Stowsky says his school may adopt “more hybrid instruction – some students physically in class, with simultaneous remote broadcasting (eg, via Zoom), and asynchronous lecturer capture for students in different time zones”.

A Canadian leader remains hopeful, however, that while “the fear of being stranded far away and the need for local supplies and solutions will be with us for some time, the academic community will continue to be the portal to the bigger world. The universities that will be most competitive are the ones that figure out best how to personalise remote learning, ramp-in students to in-person activities safely and connect their students to a place and community.”

There is a common sense among respondents that universities will need to walk the tightrope between increased online provision and a continuing focus on the value of in-person provision. For instance, a Japanese leader foresees that online education will “lead to a rapid expansion not only of domestic demand, but also the demand among students from countries in Africa and Asia, where population explosion is expected in the future”. By the same token, “if we can create an attractive curriculum that students can’t learn unless they come to Japan, business opportunities at universities will expand.”

But Japan is generally unenthusiastic about increased use of blended learning. Overall, 84 per cent of respondents say that their experience of mass online teaching during the lockdowns, and the realisation of its possibilities, will increase their use of blended learning over the next five years. The figure is above 90 per cent in Oceania, Europe, North America and South Asia, but only 36 per cent in Japan – although the International Christian University is contemplating adopting “online ‘units’, which may constitute course requirement for degree”, says Iwakiri.

In many countries, moreover, doubt remains that online interaction can fully replace the face-to-face variety. “Online learning will become an integral part of our course delivery, but it won’t be exclusive,” says the Polytechnic University of Milan’s Resta. “Online learning is useful to share knowledge…but it cannot take the place of human interaction, empathy, critical thinking, teamwork and cooperative design.” And a compatriot adds: “We should not forget that teaching online is not the most appropriate way of teaching, particularly in high-level courses, and that we are using it only for emergency reasons.”

Some leaders also reiterate the fact that while, in principle, online education opens up access to people wherever they live, in reality it restricts it to those whose home environment is conducive to learning. Among our respondents, 37 per cent fear that a switch to more online teaching would lead to lower student retention, against 29 per cent who disagree, although 36 per cent are unsure.

Nor is access the only potential student-related issue. One university leader fears higher dropout rates simply by virtue of the fact that “the campus environment does play a significant role in attracting and retaining students”.

A longer-term online switch might also be thought to have big potential implications for university finances and staffing levels. However, university leaders typically downplay them. Only 17 per cent expect that it would reduce the need for professional staff; the comment of Peter Slee, vice-chancellor of Leeds Beckett University, is typical: “It may change the balance but not the numbers.”

Even fewer respondents – just 11 per cent – expect that online teaching will reduce the need for academic staff. A Canadian leader notes that even if more online teaching were adopted, “we would still want to offer small class sizes”. And a Chinese university leader explains that “teachers are the most active and dynamic factor in academic organisations. Online teaching is only a tool to assist teaching: it cannot replace the production and creation of knowledge by people.”

But Slee adds that an online shift “will lead to us valuing different skills in our teachers. Content delivery is less important now than developing understanding and application of what is learnt.”

The ongoing need for high staffing levels no doubt explains why only 22 per cent of respondents expect that more online teaching would improve universities’ financial positions, against 43 per cent who disagree. But nor do respondents believe that it would drive down tuition fees (thereby hitting institutional finances). Just 21 per cent have that expectation, with scepticism especially strong in Japan, China and North America. “The assumption [of the question] is that online teaching does not involve a campus experience and/or is of lower quality,” says an Australian vice-chancellor. “In a blended environment, neither is true and the cost base is no lower.”

By contrast, leaders in Mena and South Asia are more inclined to believe that online provision would indeed drive down tuition fees.

Research

Of course, the questions raised for universities by the pandemic are not merely financial. Another one is about their role in society. In particular, is their research focused in the right areas?

The obvious discipline whose importance has been underlined by the global craving for a Covid-19 vaccine is biomedicine, and many respondents intend to do more of it in future. Other pandemic-related issues are also frequently mentioned as areas for future research. For instance, the National Yunlin University of Science and Technology in Taiwan also plans to investigate “epidemic prevention, crisis management, zero-contact manufacturing and service delivery” as well as “online learning effectiveness”. Egypt’s University of Sadat City plans to focus on “how to overcome the negative economic, social and political impacts of the coronavirus”. And a Chinese leader suggests that “the internet’s impact on styles of work and life” will also be a good topic to explore.

Some respondents note that changes may be forced on universities by the changing requirements of funders. Bucks New University, for instance, will pursue “greater alignment to national priorities, which will shift towards health and social care and a focus on economic recovery”, according to Braisby.

Most respondents agree that science will become a higher priority for their governments post-Covid; 62 per cent agree, against only 8 per cent who disagree. However, there is some scepticism from North America: “Politicians have short attention spans,” notes John Kraft, president of the University of Florida. “It really depends on whether we have government leadership that believes in science,” adds another US president.

Global confidence is also reasonably high that political prioritisation of science will translate into funding increases from public and/or charitable sources; 44 per cent agree that it will, against 23 per cent who disagree.

Confidence is especially high in Asia in general and in China most of all, where 74 per cent expect a rising research budget, against 4 per cent who do not. By contrast, no respondents from Oceania expect a funding rise, while 67 per cent do not expect one. However, many leaders are unsure what to expect. “I hope [for a rise], but it is too early to say” is a typical comment, this one from an Italian rector.

Respondents are more confident that international collaboration in science and research will be strengthened by the pandemic. Overall, 60 per cent have this expectation, compared with 12 per cent who do not, with confidence highest in Mena (79 per cent). “The pandemic makes us recognise more strongly that this type of problem needs international collaboration in science and research,” notes the International Christian University’s Iwakiri.

Confidence is lowest in the UK – which is faced with the fallout from Brexit – and the US and China, whose interaction has been hit by the Trump administration’s clampdown on collaboration between the geopolitical rivals. This is reflected in some respondents’ comments. Increased international collaboration “partly depends on whether Trump is re-elected” in November, notes Berkeley’s Stowsky, while an Australian vice-chancellor predicts that the US-China standoff will “force other nations to ‘take sides’”.

The Trump administration, for instance, has involved US universities in its war of words with China over the coronavirus, such as by warning of Chinese attempts to steal US research into potential vaccines. On the other hand, a Chinese leader believes that China’s virus prevention and control measures have amply demonstrated China’s “scientific research strength and institutional advantages. This will attract more foreign students to study in China; Chinese students will also be more confident to stay in their home country to study.”

It is certainly very clear which country university leaders consider has handled the coronavirus outbreak most and least successfully from a public health perspective. New Zealand’s “go hard, go early” approach draws the most plaudits (21 per cent), followed by mainland China (18 per cent). And the least successful? The US is the overwhelming choice, garnering 66 per cent of nominations.

No doubt the US’ high international prominence partly explains this result. But if international students’ choices of destination are affected, at least for a few years, by perceptions of countries’ ability to control the spread of the virus, it seems that the US colleges and universities that rely on their fees may have more to fear than most.

Click here to see full results of survey

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Will the pandemic blight universities’ future?

If you would like to discuss the results of this survey further, and explore how our analysis can contribute to your institution’s strategic response to Covid-19, please contact Elizabeth Shepherd, head of THE’s consultancy team, at Elizabeth.Shepherd@timeshighereducation.com

0 Comments