Is COVID-19 widening educational gaps in Latin America? Three lessons for urgent policy action

Is COVID-19 widening educational gaps in Latin America? Three lessons for urgent policy action

By Nathalie Basto-Aguirre, Paula Cerutti and Sebastián Nieto-Parra, OECD Development Centre

This blog is part of a series on tackling COVID-19 in developing countries. Visit the OECD dedicated page to access the OECD’s data, analysis and recommendations on the health, economic, financial and societal impacts of COVID-19 worldwide.

COVID-19, like most crises, is exacerbating inequalities in the region. To contain the pandemic, most Latin American countries have closed their schools, affecting the learning of 154 million students. However, not all students are affected equally. While distance education can contribute to alleviate the immediate impacts of school closures, it requires a number of conditions to deliver meaningful results. Students from poorer socio-economic backgrounds tend to suffer the most and risk bearing lasting consequences in terms of learning outcomes and, ultimately, opportunities. In particular, three interconnected dimensions stand out.

First, the impact of school closures on students varies according to the readiness of schools, principals and teachers to “go digital”. Few schools were adequately equipped for digital learning before the pandemic in the region. Based on PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) 2018 results, only one third of the region’s 15-year-old students have access to an effective online learning support platform at school compared to almost two thirds in OECD countries[1]. Socio-economic differences are vast: only 20% of 15-year-old students attending disadvantaged schools can access an effective online learning support platform, compared to 50% of those attending advantaged schools.

Furthermore, the difference in digital readiness between socio-economically disadvantaged and advantaged schools is particularly striking when it comes to delivering distance education through digital tools. For example, in Argentina, Brazil and Colombia the gap is more than 20 percentage points (vs. less than 10 percentage points in OECD countries). The slow incorporation of digital tools into learning has limited the development of skills that, with schools closed, are needed to design and implement alternative learning strategies that use Information and Communications Technology (ICTs).

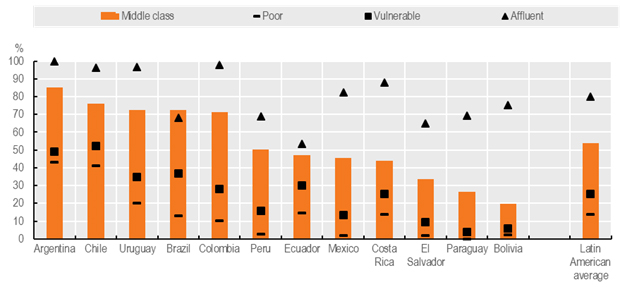

Second, school closures affect households differently depending on their access and use of digital devices. The pandemic has shed light on the persistent digital divide in Latin American households. Only 34% of primary, 41% of secondary and 68% of tertiary education students have access to an Internet-connected computer at home[2]. Studying online is difficult for students from poor and vulnerable households. For instance, less than 14% of poor students (those living with less than USD 5.5 per day, PPP 2011) in primary education have a computer connected to the Internet at home vs. more than 80% of affluent students (i.e. those living with more than USD 70 per day, in PPP 2011 terms) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of students enrolled in primary education with an Internet-connected computer at home by income group, latest available data

Note: The regional average is a simple average. Poor are those living with less than USD 5.5 per capita per day (PPP 2011). Vulnerable those living with USD 5.5 to USD 13 per capita per day (PPP 2011). Middle-class those living with USD 13 to USD 70 per capita day (PPP 2011). And, affluent those living with more than USD 70 per capita per day (PPP 2011).

Source: OECD Development Centre calculations based on each country’s latest available Household Surveys.

Third, school closures significantly affect students in households with less reliable support from their parents. Parents’ skills and their capacity to help students use technology for learning contribute to widening gaps. Advantaged students are more likely to have parents with higher levels of cognitive and digital skills who can support distance learning. In the region, most of the poorest parents have not finished secondary school and rarely use ICTs other than mobile phones. In Argentina, for example, only two out of five adults living with primary school students in the poorest decile of income distribution have a secondary degree and one out of five used a computer in the last three months. In contrast, almost all adults living with primary school students in the richest decile completed secondary education and more than four out of five used a computer in the last three months.

These three dimensions put extra pressure on the region’s long-standing socio-economic educational gap.

Although the pandemic’s effects on education are not yet measurable, it is possible to make an informed guess. Advantaged students, usually among the top performers, will probably continue learning almost as if schools were open. On the other hand, disadvantaged students, usually among the worst performers, could fall further behind. In fact, disadvantaged students tend to experience bigger learning losses when out of school, for example during vacation or teacher strikes. On average across subjects and grades, poor students lose about three more months of learning than their middle-income peers do every summer, due mainly to lack of educational material at home. This is being replicated during lockdowns.

To overcome both school closures and the digital divide during the COVID-19 crisis, school systems in the region have drawn on their experiences in reaching remote areas. Education leaders and teachers, in close collaboration with local authorities and the private sector, have expanded access to the Internet in specific zones and provided students with ICT tools. They have also combined online platform learning with WhatsApp, mobile or social media, traditional media (television, radio) and printed materials delivered to students and parents without Internet access.

Countries should strengthen these efforts and take urgent action, at least on three fronts. First, COVID-19 has shed light on the fact that not all education systems and schools are equally prepared to ensure remote learning. Online learning support from schools to students, including teacher training, must be improved (some good practices compiled by the OECD and the World Bank can be found here and here). Second, digital technology only translates into better education performance for students who have access to ICTs and have been able to develop strong cognitive and digital skills. To reduce inequalities, all students must have access to digital infrastructure, facilities, equipment and content (analysed in the forthcoming OECD/CAF/ECLAC/EC Latin American Economic Outlook 2020). However, access is not enough. Targeted support is necessary for less advantaged students and their families to benefit from technology by building foundational, cognitive and digital skills. Finally, students’ socio-economic backgrounds shape how they learn at home. Today, more than ever, targeted income and non-monetary support is needed for the most vulnerable segments of society (for example by expanding coverage of social protection to informal workers). Good policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis can accelerate transformation in education systems and reduce socio-economic disparities with positive and lasting effects.

[1] Latin American average figures refer to simple averages on countries participating in PISA 2018: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama, Peru and Uruguay.

[2] Latin American average figures refer to simple averages on countries that ask about ICT in their nationally representative household survey. Countries covered are Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay.

0 Comments