Karl Marx’s theory of history has not been borne out. And yet, even where Marx was wrong, his ideas still serve – 200 years after his birth – as a reference point for thinking about the politics of work, inequality, globalization, and new technology.

Is Marx Still Relevant?

MELBOURNE – From 1949, when Mao Zedong’s communists triumphed in China’s civil war, until the collapse of the Berlin Wall 40 years later, Karl Marx’s historical significance was unsurpassed. Nearly four of every ten people on earth lived under governments that claimed to be Marxist, and in many other countries Marxism was the dominant ideology of the left, while the policies of the right were often based on how to counter Marxism.

Once communism collapsed in the Soviet Union and its satellites, however, Marx’s influence plummeted. On the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth on May 5, 1818, it isn’t far-fetched to suggest that his predictions have been falsified, his theories discredited, and his ideas rendered obsolete. So why should we care about his legacy in the twenty-first century?1

Marx’s reputation was severely damaged by the atrocities committed by regimes that called themselves Marxist, although there is no evidence that Marx himself would have supported such crimes. But communism collapsed largely because, as practiced in the Soviet bloc and in China under Mao, it failed to provide people with a standard of living that could compete with that of most people in the capitalist economies.

These failures do not reflect flaws in Marx’s depiction of communism, because Marx never depicted it: he showed not the slightest interest in the details of how a communist society would function. Instead, the failures of communism point to a deeper flaw: Marx’s false view of human nature.

There is, Marx thought, no such thing as an inherent or biological human nature. The human essence is, he wrote in his Theses on Feuerbach, “the ensemble of the social relations.” It follows then, that if you change the social relations – for example, by changing the economic basis of society and abolishing the relationship between capitalist and worker – people in the new society will be very different from the way they were under capitalism.

Marx did not arrive at this conviction through detailed studies of human nature under different economic systems. It was, rather, an application of Hegel’s view of history. According to Hegel, the goal of history is the liberation of the human spirit, which will occur when we all understand that we are part of a universal human mind. Marx transformed this “idealist” account into a “materialist” one, in which the driving force of history is the satisfaction of our material needs, and liberation is achieved by class struggle. The working class will be the means to universal liberation because it is the negation of private property, and hence will usher in collective ownership of the means of production.

Once workers owned the means of production collectively, Marx thought, the “springs of cooperative wealth” would flow more abundantly than those of private wealth – so abundantly, in fact, that distribution would cease to be a problem. That is why he saw no need to go into detail about how income or goods would be distributed. In fact, when Marx read a proposed platform for a merger of two German socialist parties, he described phrases like “fair distribution” and “equal right” as “obsolete verbal rubbish.” They belonged, he thought, to an era of scarcity that the revolution would bring to an end.

The Soviet Union proved that abolishing private ownership of the means of production does not change human nature. Most humans, instead of devoting themselves to the common good, continue to seek power, privilege, and luxury for themselves and those close to them. Ironically, the clearest demonstration that the springs of private wealth flow more abundantly than those of collective wealth can be seen in the history of the one major country that still proclaims its adherence to Marxism.

Under Mao, most Chinese lived in poverty. China’s economy started to grow rapidly only after 1978, when Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping (who had proclaimed that, “It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice”) allowed private enterprises to be established. Deng’s reforms eventually lifted 800 million people out of extreme poverty, but also created a society with greater income inequality than any European country (and much greater than the United States). Although China still proclaims that it is building “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” it is not easy to see what is socialist, let alone Marxist, about its economy.

If China is no longer significantly influenced by Marx’s thought, we can conclude that in politics, as in economics, he is indeed irrelevant. Yet his intellectual influence remains. His materialist theory of history has, in an attenuated form, become part of our understanding of the forces that determine the direction of human society. We do not have to believe that, as Marx once incautiously put it, the hand-mill gives us a society with feudal lords, and the steam-mill a society with industrial capitalists. In other writings, Marx suggested a more complex view, in which there is interaction among all aspects of society.

The most important takeaway from Marx’s view of history is negative: the evolution of ideas, religions, and political institutions is not independent of the tools we use to satisfy our needs, nor of the economic structures we organize around those tools, and the financial interests they create. If this seems too obvious to need stating, it is because we have internalized this view. In that sense, we are all Marxists now.

Marx and the Mechanical Turk

BERKELEY – The economist Suresh Naidu once remarked to me that there were three big problems with Karl Marx’s economics. First, Marx thought that increased investment and capital accumulation diminished labor’s value to employers and thus diminished workers’ bargaining power. Second, he could not fully grasp that rising real material living standards for the working class might well go hand in hand with a rising rate of exploitation – that is, a smaller income share for labor. And, third, Marx was fixated on the labor-theory of value.

The second and third problems remain huge analytical mistakes. But, while Marx’s belief that capital and labor were substitutes, not complements, was a mistake in his own age, and for more than a century to follow, it may not be a mistake today.

Think of it this way. Humans have five core competencies as far as the world of work is concerned:

· Moving things with large muscles.

· Finely manipulating things with small muscles.

· Using our hands, mouths, brains, eyes, and ears to ensure that ongoing processes and procedures happen the way that they are supposed to.

· Engaging in social reciprocity and negotiation to keep us all pulling in the same direction.

· Thinking up new things – activities that produce outcomes that are necessary, convenient, or luxurious – for us to do.

The first two options comprise jobs that we typically think of as “blue collar.” Much of the second three options embody jobs that we typically think of as “white collar.”

The coming of the Industrial Revolution – the steam engine to generate power and metalworking to build machinery – greatly reduced the need for human muscles and fingers. But it enormously increased the need for human eye-ear-brain-hand-mouth loops in both blue-collar and white-collar occupations.

Over time, the real prices of machines continued to fall. But the real prices of the cybernetic control loops needed to keep the machines running properly did not, because every control loop required a human brain, and every human brain required a fifteen-year process of growth, education, and development.

But there is no iron law of wages that requires technologies of power and matter manipulation to advance more rapidly than technologies of governance and control. The direction of technological progress today is toward moving very large parts of both the blue-collar and white-collar components of overseeing ongoing processes and procedures from humans to machines.

How many of us can be employed in personal services, and how can such jobs be highly paid (in absolute terms)? The optimistic view is that those, like me, who find ourselves fearing the relative wage distribution of the future as a source of mammoth inequality and power imbalance simply suffer from a failure of imagination.

Marx did not see how the replacement of textile workers by automatic looms could possibly do anything other than lower workers’ wages. After all, the volume of production could not possibly expand enough to reemploy everyone who lost their job as a handloom weaver as a machine-minder or a carpet-seller, could it?

It could, but Marx’s mistake was not a new one. A century earlier, the French physiocrats Quesnay, Turgot, and Condorcet did not see how the share of the French labor force employed in agriculture could possibly fall below 50% without producing social ruin. After all, in a world of solid farmers, useful craftsmen, dissolute aristocrats, and flunkies, demand for manufactured items and flunkies was limited by how much of each aristocrats could use. Thus, a decline in the number of farmers could produce no outcome other than poverty and widespread beggary.

Neither Marx nor the physiocrats could imagine the great many well-paid things that we could find to do once we no longer needed to employ 60% of the labor force in agriculture and another 20% in hand spinning, handloom weaving, and land transport via horse and cart. And today, the optimistic view is that those with excess wealth will continue to think of lots of things for everyone else to do to make their lives more convenient and luxurious, and that the ingenuity of the rich will outstrip the supply of labor by the poor and turn the poor into the middle class.

But, given the rapid development of technologies of governance and control, the pessimistic view deserves attention. In this scenario, pieces of option three remain stubbornly impervious to artificial intelligence and continue to be mind-numbingly boring, while option four – engaging in social reciprocity and negotiation – remains limited. Welcome to the virtual sweatshop economy, in which most of us are chained to desks and screens – so many powerless cogs for Amazon Mechanical Turk, forever.

Editor’s note: A shorter version of this commentary was previously published by the New York Times.

Malthus, Marx, and Modern Growth

CAMBRIDGE – The promise that each generation will be better off than the last is a fundamental tenet of modern society. By and large, most advanced economies have fulfilled this promise, with living standards rising over recent generations, despite setbacks from wars and financial crises.

In the developing world, too, the vast majority of people have started to experience sustained improvement in living standards and are rapidly developing similar growth expectations. But will future generations, particularly in advanced economies, realize such expectations? Though the likely answer is yes, the downside risks seem higher than they did a few decades ago.

So far, every prediction in the modern era that mankind’s lot will worsen, from Thomas Malthus to Karl Marx, has turned out to be spectacularly wrong. Technological progress has trumped obstacles to economic growth. Periodic political rebalancing, sometimes peaceful, sometimes not, has ensured that the vast majority of people have benefited, albeit some far more than others.

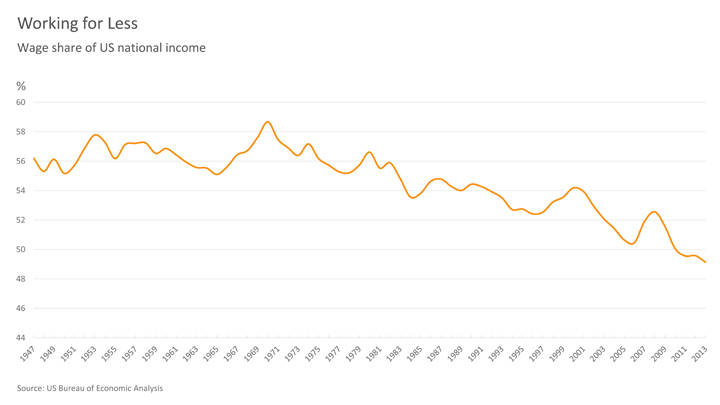

As a result, Malthus’s concerns about mass starvation have failed to materialize in any peaceful capitalist economy. And, despite a disconcerting fall in labor’s share of income in recent decades, the long-run picture still defies Marx’s prediction that capitalism would prove immiserating for workers. Living standards around the world continue to rise.

But past growth performance is no guarantee that a broadly similar trajectory can be maintained throughout this century. Leaving aside potential geopolitical disruptions, there are some formidable challenges to overcome, mostly stemming from political underperformance and dysfunction.

The first set of issues includes slow-burn problems involving externalities, the leading example being environmental degradation. When property rights are ill-defined, as in the case of air and water, government must step in to provide appropriate regulation. I do not envy future generations for having to address the possible ramifications of global warming and fresh-water depletion.

A second set of problems concerns the need to ensure that the economic system is perceived as fundamentally fair, which is the key to its political sustainability. This perception can no longer be taken for granted, as the interaction of technology and globalization has exacerbated income and wealth inequality within countries, even as cross-country gaps have narrowed.

Until now, our societies have proved remarkably adept at adjusting to disruptive technologies; but the pace of change in recent decades has caused tremendous strains, reflected in huge income disparities within countries, with near-record gaps between the wealthiest and the rest. Inequality can corrupt and paralyze a country’s political system – and economic growth along with it.

The third problem is that of aging populations, an issue that would pose tough challenges even for the best-designed political system. How will resources be allocated to care for the elderly, especially in slow-growing economies where existing public pension schemes and old-age health plans are patently unsustainable? Soaring public debts surely exacerbate the problem, because future generations are being asked both to service our debt and to pay for our retirements.

The final challenge concerns a wide array of issues that require regulation of rapidly evolving technologies by governments that do not necessarily have the competence or resources to do so effectively. We have already seen where poor regulation of rapidly evolving financial markets can lead. There are parallel shortcomings in many other markets.

A leading example is food supply – an area where technology has continually produced ever-more highly processed and genetically refined food that scientists are only beginning to assess. What is known so far is that childhood obesity has become an epidemic in many countries, with an alarming rise in rates of type 2 diabetes and coronary disease implying a significant negative impact on life expectancy in future generations.

Many leading health researchers, including Kelly Brownell, David Ludwig, and Walter Willett, have documented these problems. Government interventions to date, mainly in the form of enhanced education, have proved largely ineffective. Self-destructive addiction to processed foods, which economists would describe as an “internality,” can lower quality of life for those afflicted, and can eventually lead to externalities for society, such as higher health-care costs. Again, despite a rising chorus of concern from researchers, political markets have seemed frozen.

All of these problems have solutions, at least in the short to medium run. A global carbon tax would mitigate climate risks while alleviating government debt burdens. Addressing inequality requires greater redistribution through national tax systems, together with enhanced programs for adult education, presumably making heavy use of new technologies. The negative effects of falling population growth can be mitigated by easing restrictions on international migration, and by encouraging more women and retirees to enter or stay in the workforce. But how long it will take for governments to act is a wide-open question.

Capitalist economies have been spectacularly efficient at enabling growing consumption of private goods, at least over the long run. When it comes to public goods – such as education, the environment, health care, and equal opportunity – the record is not quite as impressive, and the political obstacles to improvement have seemed to grow as capitalist economies have matured.

Will each future generation continue to enjoy a better quality of life than its immediate predecessor? In developing countries that have not yet reached the technological frontier, the answer is almost certainly yes. In advanced economies, though the answer should still be yes, the challenges are becoming formidable.

Liberal Totalitarianism

LISBON – It used to be an axiom of liberalism that freedom meant inalienable self-ownership. You were your own property. You could lease yourself to an employer for a limited period, and for a mutually agreed price, but your property rights over yourself could not be bought or sold. Over the past two centuries, this liberal individualist perspective legitimized capitalism as a “natural” system populated by free agents.

A capacity to fence off a part of one’s life, and to remain sovereign and self-driven within those boundaries, was paramount to the liberal conception of the free agent and his or her relationship with the public sphere. To exercise freedom, individuals needed a safe haven within which to develop as genuine persons before relating – and transacting – with others. Once constituted, our personhood was to be enhanced by commerce and industry – networks of collaboration across our personal havens, constructed and revised to satisfy our material and spiritual needs.

But the dividing line between personhood and the external world upon which liberal individualism based its concepts of autonomy, self-ownership, and, ultimately, freedom could not be maintained. The first breach appeared as industrial products became passé and were replaced by brands that captured the public’s attention, admiration, and desire. Before long, branding took a radical new turn, imparting “personality” to objects.

Once brands acquired personalities (boosting consumer loyalty immensely and profits accordingly), individuals felt compelled to re-imagine themselves as brands. And today, with colleagues, employers, clients, detractors, and “friends” constantly surveying our online life, we are under incessant pressure to evolve into a bundle of activities, images, and dispositions that amounts to an attractive, sellable brand. The personal space essential to the autonomous development of an authentic self – the condition that makes inalienable self-ownership possible – is now almost gone. The habitat of liberalism is disappearing.

That habitat’s clear demarcation of private and public spheres also divided leisure from work. One need not be a radical critic of capitalism to see that the right to a time when one is not for sale is all but gone, too.

Consider young people striking out in the world today. For the most part, those without a trust fund or generous unearned income end up in one of two categories. The many are condemned to labor under zero-hour contracts and wages so low that they must work all available hours to make ends meet, rendering offensive any talk of personal time, space, or freedom.

The rest are told that, to avoid falling into this soul-destroying “precariat,” they must invest in their own brand every waking hour of every day. As if in a Panopticon, they cannot hide from the attention of those who might give them a break (or know others who might). Before posting any tweet, watching any movie, sharing any photograph or chat message, they must remain mindful of the networks they please or alienate.

When lucky enough to be granted a job interview, and land the job, the interviewer alludes immediately to their expendability. “We want you to be true to yourself, to follow your passions, even if this means we must let you go!” they are told. So they redouble their efforts to discover “passions” that future employers may appreciate, and to locate that mythical “true” self that people in positions of power tell them is somewhere inside them.

Their quest knows no bounds and respects no limits. John Maynard Keynes once famously used the example of a beauty contest to explain the impossibility of ever knowing the “true” value of shares. Stock-market participants are uninterested in judging who the prettiest contestant is. Instead, their choice is based on a prediction of who average opinion believes is the prettiest, and what average opinion thinks average opinion is – thus ending up like cats chasing after their own tails.

Keynes’s beauty contest sheds light on the tragedy of many young people today. They try to work out what average opinion among opinion-makers believes is the most attractive of their own potential “true” selves, and simultaneously struggle to manufacture this “true” self online and offline, at work and at home – indeed, everywhere and always. Entire industries of counselors and coaches, and varied ecosystems of substances and self-help, have emerged to guide them on this quest.

The irony is that liberal individualism seems to have been defeated by a totalitarianism that is neither fascist nor communist, but which grew out of its own success at legitimizing the encroachment of branding and commodification into our personal space. To defeat it, and thus rescue the liberal idea of freedom as self-ownership, may require a comprehensive reconfiguration of property rights over the increasingly digitized instruments of production, distribution, collaboration, and communication.

Would it not be a splendid paradox if, 200 years after the birth of Karl Marx, we decided that, in order to save liberalism, we must return to the idea that freedom demands the end of unfettered commodification and the socialization of property rights over capital goods?

Is Capitalism Doomed?

NEW YORK – The massive volatility and sharp equity-price correction now hitting global financial markets signal that most advanced economies are on the brink of a double-dip recession. A financial and economic crisis caused by too much private-sector debt and leverage led to a massive re-leveraging of the public sector in order to prevent Great Depression 2.0. But the subsequent recovery has been anemic and sub-par in most advanced economies given painful deleveraging.

Now a combination of high oil and commodity prices, turmoil in the Middle East, Japan’s earthquake and tsunami, eurozone debt crises, and America’s fiscal problems (and now its rating downgrade) have led to a massive increase in risk aversion. Economically, the United States, the eurozone, the United Kingdom, and Japan are all idling. Even fast-growing emerging markets (China, emerging Asia, and Latin America), and export-oriented economies that rely on these markets (Germany and resource-rich Australia), are experiencing sharp slowdowns.

Until last year, policymakers could always produce a new rabbit from their hat to reflate asset prices and trigger economic recovery. Fiscal stimulus, near-zero interest rates, two rounds of “quantitative easing,” ring-fencing of bad debt, and trillions of dollars in bailouts and liquidity provision for banks and financial institutions: officials tried them all. Now they have run out of rabbits.

Fiscal policy currently is a drag on economic growth in both the eurozone and the UK. Even in the US, state and local governments, and now the federal government, are cutting expenditure and reducing transfer payments. Soon enough, they will be raising taxes.

Another round of bank bailouts is politically unacceptable and economically unfeasible: most governments, especially in Europe, are so distressed that bailouts are unaffordable; indeed, their sovereign risk is actually fueling concern about the health of Europe’s banks, which hold most of the increasingly shaky government paper.

Nor could monetary policy help very much. Quantitative easing is constrained by above-target inflation in the eurozone and UK. The US Federal Reserve will likely start a third round of quantitative easing (QE3), but it will be too little too late. Last year’s $600 billion QE2 and $1 trillion in tax cuts and transfers delivered growth of barely 3% for one quarter. Then growth slumped to below 1% in the first half of 2011. QE3 will be much smaller, and will do much less to reflate asset prices and restore growth.

Currency depreciation is not a feasible option for all advanced economies: they all need a weaker currency and better trade balance to restore growth, but they all cannot have it at the same time. So relying on exchange rates to influence trade balances is a zero-sum game. Currency wars are thus on the horizon, with Japan and Switzerland engaging in early battles to weaken their exchange rates. Others will soon follow.

Meanwhile, in the eurozone, Italy and Spain are now at risk of losing market access, with financial pressures now mounting on France, too. But Italy and Spain are both too big to fail and too big to be bailed out. For now, the European Central Bank will purchase some of their bonds as a bridge to the eurozone’s new European Financial Stabilization Facility. But, if Italy and/or Spain lose market access, the EFSF’s €440 billion ($627 billion) war chest could be depleted by the end of this year or early 2012.

Then, unless the EFSF pot were tripled – a move that Germany would resist – the only option left would become an orderly but coercive restructuring of Italian and Spanish debt, as has happened in Greece. Coercive restructuring of insolvent banks’ unsecured debt would be next. So, although the process of deleveraging has barely started, debt reductions will become necessary if countries cannot grow or save or inflate themselves out of their debt problems.

So Karl Marx, it seems, was partly right in arguing that globalization, financial intermediation run amok, and redistribution of income and wealth from labor to capital could lead capitalism to self-destruct (though his view that socialism would be better has proven wrong). Firms are cutting jobs because there is not enough final demand. But cutting jobs reduces labor income, increases inequality and reduces final demand.

Recent popular demonstrations, from the Middle East to Israel to the UK, and rising popular anger in China – and soon enough in other advanced economies and emerging markets – are all driven by the same issues and tensions: growing inequality, poverty, unemployment, and hopelessness. Even the world’s middle classes are feeling the squeeze of falling incomes and opportunities.

To enable market-oriented economies to operate as they should and can, we need to return to the right balance between markets and provision of public goods. That means moving away from both the Anglo-Saxon model of laissez-faire and voodoo economics and the continental European model of deficit-driven welfare states. Both are broken.

The right balance today requires creating jobs partly through additional fiscal stimulus aimed at productive infrastructure investment. It also requires more progressive taxation; more short-term fiscal stimulus with medium- and long-term fiscal discipline; lender-of-last-resort support by monetary authorities to prevent ruinous runs on banks; reduction of the debt burden for insolvent households and other distressed economic agents; and stricter supervision and regulation of a financial system run amok; breaking up too-big-to-fail banks and oligopolistic trusts.

Over time, advanced economies will need to invest in human capital, skills and social safety nets to increase productivity and enable workers to compete, be flexible and thrive in a globalized economy. The alternative is – like in the 1930s – unending stagnation, depression, currency and trade wars, capital controls, financial crisis, sovereign insolvencies, and massive social and political instability.

0 Comments