The University of California System remains a model blueprint despite Berkeley’s travails, and one the UK would do well to copy, says Alan Ryan

-

By Alan Ryan

Whenever I argue that the UK – or at any rate England and Wales – should plagiarise the California Master Plan for Higher Education, I get two responses. They contradict one another, but they often come from the same people, and only a minute or two apart. The first is that it wouldn’t suit the UK, so it’s an absurd idea; the second is that it would be wonderful, but it’s too late to implement it.

It is certainly late in the day to be arguing that what the UK needs is not the latest Green Paper, ever-higher tuition fees and increasingly desperate attempts to measure teaching quality but rather a return to the basics, as understood in California 55 years ago. And now might seem a particularly odd time to try to make the case, given the depth of the financial problems faced by Berkeley and the other University of California campuses.

Just last month, Berkeley chancellor Nicholas Dirks said in a memo to staff that funding cuts mean that the institution faces “a substantial and growing structural deficit” that requires a radical overhaul of its expenditure. “What we are engaged in here is a fundamental defense of the concept of the public university: a concept that we must reinvent in order to preserve,” he said. And while he stressed that educational quality would be prioritised, he warned that the realignment would inevitably be “painful”, leading some to question whether Berkeley could maintain its standing as a leading global research university. Berkeley’s problems reflect the same political realities as in the UK. Governments addicted to so-called austerity won’t spend money on intellectual infrastructure, even though they know that they are piling up problems for the future. They preach the value of education while making it increasingly impossible to deliver.

But, whatever the current fiscal realities, the rationale for the California System remains just as compelling now as it was in the 1950s. Properly funded, the plan provides high-grade vocational education alongside education for its own sake; it allows progression from one level of the system to another; it offers opportunities for students to explore higher education without incurring disastrous debts via tuition loans; and it offers a way back in to higher education for mature students.

The Master Plan was passed into law in 1960, when Pat Brown, the father of the present California governor, Jerry Brown, was governor of the Golden State. It was in large part the brainchild of Clark Kerr, the president of the University of California and, before that, the chancellor of Berkeley. The crucial elements were an integrated, tripartite public higher education system with different institutions playing different but connected roles. There would be open access at the base via community colleges, spread across the state to serve every locality. These were bolted into the higher education system by being given their own governing board, detaching them from a state education board that was preoccupied with primary and secondary education.

No tuition fees were to be charged, and there were to be clear routes to the more selective parts of the system. The state colleges were to become California State University. Hitherto, they had largely been teacher training institutions, but they were now expected to teach up to MA level in almost any field where there was a demand. They were not to undertake “pure” research, but there was a hope (largely unfulfilled) that students might get a PhD from a state university in combination with one of the University of California institutions or an accredited private doctoral institution. The University of California campuses were to undertake pure research across the board, and their success in doing so hardly needs emphasising. There are five University of California campuses in the top 50 of Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings 2015-2016, headed by Berkeley at 13 and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) at 16.

There are currently about 240,000 undergraduates at the University of California, some 450,000 students at the 23 state university campuses, and 2.3 million at the 112 community colleges and 70-odd “centers”. But while this accounts for between two-thirds and three-quarters of all post-secondary students in California, the majority of the state’s 475 to 1,100 post-secondary institutions (the total depends on what you include) are private (especially if you plump for the latter figure). And some of these are very prestigious. They range from large universities such as Stanford University (ranked third in THE’s World University Rankings 2015-2016) through specialist science institutions such as the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) (ranked first) and liberal arts colleges such as Pomona (ranked joint fourth in US News & World Report’s college ranking) to dozens of tiny religiously affiliated colleges dedicated to training ministers and missionaries. In the past two decades, for-profit schools of variable quality have also sprung up, some of which have recently collapsed in more or less scandalous circumstances.

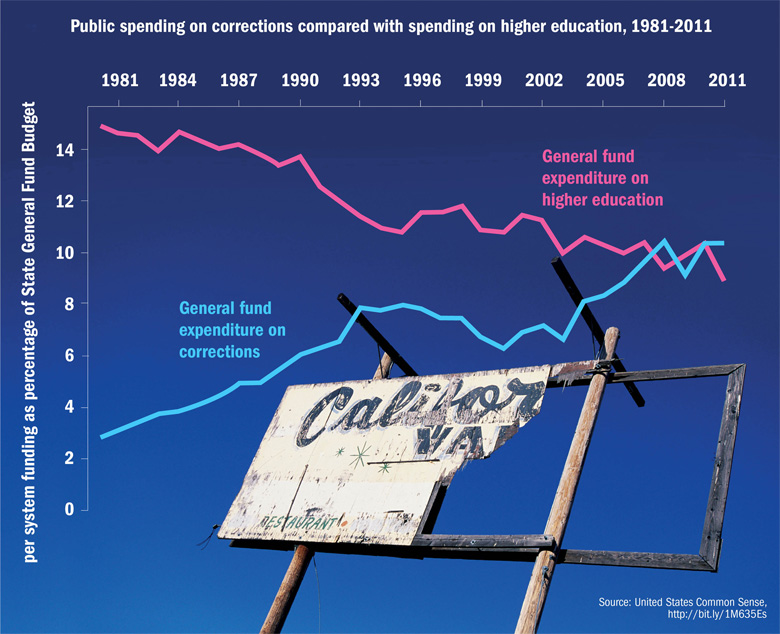

Incarceration v education: California State spending compared

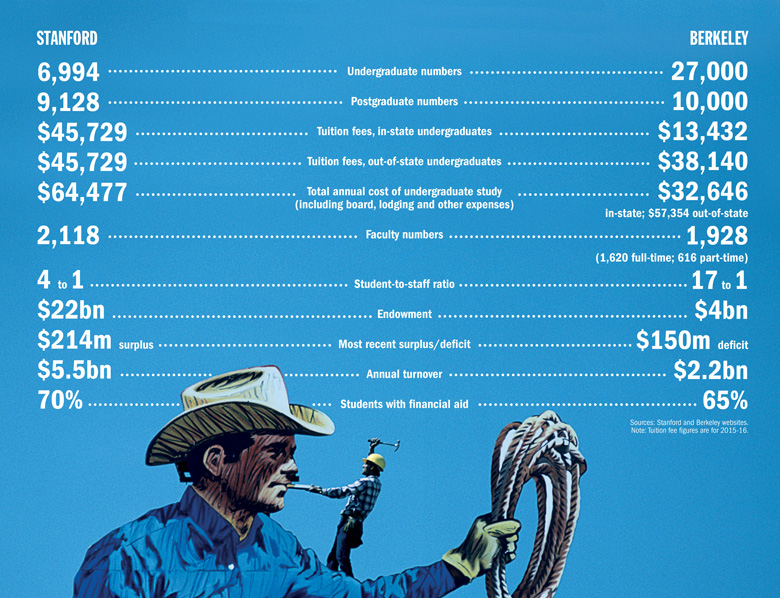

Interestingly, Kerr thought that the state should ensure the good health of a private sector that he thought should cater for about 20 per cent of students. One motive was simply to secure diversity of educational provision. Whatever Berkeley might be, it is not a liberal arts college. With 27,000 undergraduates and 10,000 postgraduates it hardly could be; Williams College in Massachusetts, with barely 2,000 students, is large by such standards. That said, other University of California institutions have squared that circle by setting up “honors colleges” offering students some of the benefits of liberal arts-style education, such as living with academically ambitious fellow students, being taught in small classes and having the chance to work on a research project in the final year. Indeed, in the late 1960s, UC Santa Cruz was set up on a collegiate basis: a mini-Oxbridge among the redwood trees. And other states, such as New York and Florida, have explicitly established liberal arts-style public institutions.

The second reason for Kerr’s wish to preserve a substantial private sector is less likely to strike a chord in British hearts. American public higher educational institutions are forbidden to attach themselves to any particular religious denomination; the constitutional separation of church and state means that public funds cannot be used for sectarian purposes. No such restrictions apply to private institutions, so students, or their parents, have to choose a private college or university if they want a non-secular education.

Many elements of the Master Plan were copied by other US states, but the full version remains unique to California. One issue has always been its cost. California had one great psychological advantage in 1960 – and a lot of financial luck. The psychological advantage was that the Master Plan – as Kerr pointed out 40 years later – was seen as a continuation of the GI Bill. In 1945, a grateful nation had been happy to pay for the higher education of returning servicemen; 15 years later, Californians were happy to pay for the higher education of their children. The financial luck was that these were the years in which the federal government threw money at higher education, especially when it looked like an investment in military defence. Peace-loving Berkeley students did well out of the fact that the university managed the Los Alamos National Laboratory – home of the Manhattan Project – along with its rival nuclear facility, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. More generally, the first dozen years of the new system were the last years of the great post-war boom, which the French call “les trente glorieuses”.

The confidence that a well-educated citizenry would be productive enough to generate the high levels of taxation that the Master Plan presupposed, and enlightened enough to understand the point of investing public funds in intellectual infrastructure, induces some nostalgia. But this confidence was not unique to California; the Robbins report that launched the UK’s plate-glass universities in the 1960s rested on the same assumptions.

The good years did not persist, however. When he became governor of California in 1967, Ronald Reagan set about getting rid of Kerr – who quipped that he left the presidency of the UC System as he had arrived: “fired with enthusiasm”. Reagan also tried to impose tuition fees on the system; he failed, but as state support dwindled, money had to be found from somewhere. The answer was much-increased “enrolment fees”: previously nominal but now a tuition fee in disguise (it was not until 1983 that “tuition” was charged under that name).

In 1978, things got worse. Most people have heard of “Proposition 13”, the measure passed by referendum that limited the amount of money that could be raised by property taxes; a companion proposition required a two-thirds majority in the legislature to increase general tax rates. These measures did not directly damage the public universities; however, community colleges and schools depend on property taxes. Indirectly, declining standards at California high schools – a slide from near the top of the national rankings to near the bottom – made the job of the higher education system that much harder. Legislation by referendum was established as a way of bringing a virtuous public opinion to bear on corrupt politicians, but it has produced the results that every critic of democracy has complained of: voters want services that they refuse to pay for, and they sacrifice their long-term interests to more immediate gratification.

Excellence on the cheap? Berkeley and Stanford compared

Of course, the old response to complaints about the cost of education remains valid: it’s nothing compared with the cost of ignorance. Criminals are generally atrociously ill-educated, and they cost a great deal more than students. But the Californian public has repeatedly demonstrated a greater willingness to pay for prisons than for universities. According to United States Common Sense, a non-profit policy group founded at Stanford, the population of incarcerated Californians grew eight times as fast as the general population between 1981 and 2011 – thanks, in part, to the notorious “three strikes” law, passed in 1994, which instituted harsher sentences for those convicted of two previous offences. Student numbers also grew, but much more slowly. About one and a half times as many were enrolled at the end of the three decades as at the beginning, while about five times as many prisoners were “enrolled”. Hence, the share of funding from general taxation going to prisons rose as that going to higher education fell (see ‘Incarceration v education: California State spending compared’ graph, above). According to CNN journalist Fareed Zakarias, California spent $9.6 billion (£6.9 billion) on prisons in 2011, compared with just $5.7 billion on higher education. This equates to just over $8,500 per student, against roughly $50,000 per inmate. There were far more students than prisoners, of course, but the numbers are pretty appalling – as is the statistic that, in the past 30 years, California had built 20 new prisons but just one new college campus.

An already fragile higher education system was hit hard by the recession of 2008. Tax revenues shrank dramatically, and the state’s grant to the higher education system was cut by 30 per cent. Faculty salaries were not only frozen, but, in 2009-10, were cut by up to 10 per cent (a similar thing happened in the early 1990s) and private universities circled UC faculty like sharks.

Things have got somewhat better since, and legislators in California are even toying with the idea of once again abolishing tuition fees at the community colleges. But nobody is happy with a situation in which tuition fees at the universities have doubled in the past five years – even if the University of California’s $12,000 fee remains less than the national average and financial aid is generous. For all his virtues, Jerry Brown is trying to square the circle; he wants UC to hold down tuition fees, restrict its intake of “out-of-state” students (who pay far higher fees) and to eliminate its deficits in return for a limited increase in state assistance. And while Janet Napolitano, current president of the University of California System and former head of the Department of Homeland Security and governor of Arizona, may insist that there is no crisis, last month’s announcement from Berkeley makes it abundantly clear that significant challenges remain to the sustainability of the system. You can’t help contrasting Stanford, swimming in cash, with Berkeley, which decidedly is not (see ‘Excellence on the cheap? Berkeley and Stanford compared’ graphic, above) – even if Berkeley dismisses Stanford as “Shallow Alto” and remains one of the world’s great universities in spite of everything.

So, what’s so wonderful about the Master Plan? It tackles four issues that the UK has failed to get right over the past half-century (some other European and Commonwealth countries do better on some of them, but the full, ambitious project is what should guide a modern system).

First, it has a vision of a higher education that is both integrated and divided by function and the level of preparation required of students. By contrast, the UK has allowed the proliferation of institutions whose pretensions outrun their ability to deliver.

Second, it embraces a level of open access that the UK – with the exception of the Open University – has never tried to match. Dropout rates at community colleges are bad, as are completion rates throughout the system, but nobody needs to pay £9,000 to discover that they don’t want to do what they have signed up for.

Third, and perhaps most important, is the easy transition that the California System permits from one level and institution to another. That would be hard to achieve in the UK, but much less hard now than in the past. Traditionally, universities ran sequentially structured degree programmes into which a system of credit accumulation would be hard to integrate. Most no longer do.

Finally, the tripartite system does what the UK has never achieved in steering a sensible line between micromanagement by government whim and giving local management scope to waste public money, irritate faculty and alienate students. Plagiarising the Master Plan would be very hard work, but a very good idea.

Alan Ryan is emeritus professor of political theory at the University of Oxford and was William H. Bonsall professor of philosophy at Stanford University in 2014-15.

0 Comments